A Formulation and Defense of the Doctrine of the Trinity

William Lane CraigSummary

After a brief historical survey of patristic Trinitarian thought, I contrast Social and "Anti-Social" Trinitarian views. A Social Trinitarian model is then presented, according to which God is a soul endowed with three sets of cognitive faculties, each sufficient for personhood. I close with a plausibility argument for God's being multi-personal.

“Let me ask of my reader, wherever, alike with myself, he is certain, there to go on with me; wherever, alike with myself, he hesitates, there to join with me in inquiring; wherever he recognizes himself to be in error, there to return to me; wherever he recognizes me to be so, there to call me back. . . . And I would make this pious and safe agreement, . . . above all, in the case of those who inquire into the unity of the Trinity, of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit; because in no other subject is error more dangerous, or inquiry more laborious, or the discovery of truth more profitable.”--Augustine, On the Trinity 1.3.5.

Introduction

One of the most noteworthy developments in contemporary philosophy of religion has been the ingress of Christian philosophers into areas normally considered the province of systematic theologians. Inasmuch as many theologians, either in the thrall of post-modernism or safely sequestered in harbor of biblical theology, have largely abdicated their traditional task of formulating and defending coherent statements of Christian doctrine, it has fallen to Christian philosophers to take up this challenge. One of the most important Christian doctrines to have attracted philosophical attention is the doctrine of the Trinity.

It is remarkable that despite the fact that its founder and earliest protagonists were to a man monotheistic Jews, Christianity, while zealous to preserve Jewish monotheism, came to enunciate a non-Unitarian concept of God. On the Christian view God is not a single person, as traditionally conceived, but is tri-personal. There are three persons, denominated the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, who deserve to be called God, and yet there is but one God, not three. This startling re-thinking of Jewish monotheism doubtless grew out of reflection on the radical self-understanding of Jesus of Nazareth himself and on the charismatic experience of the early Church. Although many New Testament critics have called into question the historical Jesus’ use of explicit Christological titles, a very strong historical case can be made for Jesus’ self-understanding as the Son of man (a divine-human eschatological figure in Daniel 7) and the unique Son of God (Matt. 11.27; Mk. 13.2; Lk. 20.9-16). Moreover, something of a consensus has emerged among New Testament critics that in his teachings and actions—such as his assertion of personal authority, his revising of the divinely given Mosaic Law, his proclamation of the in-breaking of God’s Reign or Kingdom into history in his person, his performing miracles and exorcisms as signs of the advent of that Kingdom, his Messianic pretensions to restore Israel, and his claim to forgive sins—in all these ways Jesus enunciated an implicit Christology whereby he put himself in God’s place. The German theologian Horst Georg Pöhlmann reports,

This unheard of claim to authority, as it comes to expression in the antitheses of the Sermon on the Mount, for example, is implicit Christology, since it presupposes a unity of Jesus with God that is deeper than that of all men, namely a unity of essence. This . . . claim to authority is explicable only from the side of his deity. This authority only God himself can claim. With regard to Jesus there are only two possible modes of behavior; either to believe that in him God encounters us or to nail him to the cross as a blasphemer. Tertium non datur. [1]

Moreover, the post-Easter church continued to experience the presence and power of Christ among them, despite his physical absence. Jesus himself had been a charismatic, imbued with the Spirit of God, and the Jesus movement which followed him was likewise a charismatic fellowship which experienced individually and corporately the supernatural filling and gifts of the Holy Spirit. The Spirit was thought to stand in the place of the risen and ascended Christ and to continue in his temporary absence his ministry to his people (Jn. 7.39; 14.16-17; 15.26; 16.7-16; Rom. 8.9, 10; Gal. 4.6).

In the pages of the New Testament, then, we find the raw data which the doctrine of the Trinity later sought to formulate in a systematic way. The New Testament church remained faithful to its heritage of Jewish monotheism in affirming that there is only one God (Mk 12.29; Rom. 3.29-30a; I Cor. 8.4; Jas. 2.19; I Tim. 2.5). In accord with the portrayal of God in the Old Testament (Is. 63.16) and the teaching of Jesus (Mt. 6.9), Christians also conceived of God as Father, a distinct person from Jesus His Son (Mt. 11.27; 26.39; Mk. 1.9-11; Jn. 17.5ff). Indeed, in New Testament usage, “God” (ho theos) typically refers to God the Father (e.g., Gal. 4.4-6). Now this occasioned a problem for the New Testament church: If “God” designates the Father, how can one affirm the deity of Christ without identifying him as the Father? In response to this difficulty the New Testament writers appropriated the word for God’s name (Yahweh) in the Old Testament as it appears in Greek translation in the Septuagint (kyrios = Lord) and called Jesus Lord, applying to him Old Testament proof-texts concerning Yahweh (e.g., Rom. 10.9, 13). Indeed, the confession “Jesus is Lord” was the central confession of the early church (I Cor. 12.3), and they addressed Jesus in prayer as Lord (I Cor. 16.22b). This difference-in-sameness can lead to odd locutions like Paul’s confession “we believe in one God, the Father, from whom are all things and for whom we exist, and one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom are all things and through whom we exist” (I Cor. 8.6). Furthermore, as this passage intimates, the New Testament church, not content with use of divine nomenclature for Christ, also ascribed to him God’s role as the Creator and Sustainer of all reality apart from God (Col. 1. 15-20; Heb 1.1-3; Jn 1.1-3). In places restraint is thrown to the winds, and Jesus is explicitly affirmed to be (ho)theos (Jn. 1.1, 18; 20.28; Rom. 9.5; Heb. 1.8-12; Tit. 2.13; I Jn. 5.20). Noting that the oldest Christian sermon, the oldest account of a Christian martyr, the oldest pagan report of the church, and the oldest liturgical prayer (I Cor. 16.22) all refer to Christ as Lord and God, Jaroslav Pelikan, the great historian of Christian thought, concludes, “Clearly it was the message of what the church believed and taught that ‘God’ was an appropriate name for Jesus Christ.” [2]

Finally, the Holy Spirit, who is also identified as God (Acts 5.3-4) and the Spirit of God (Mt. 12.28; I Cor. 6.11), is conceived as personally distinct from both the Father and the Son (Mt. 28.19; Lk 11.13; Jn. 14.26; 15.26; Rom. 8. 26-27; II Cor. 13.14; I Pet. 1.1-2). As these and other passages make clear, the Holy Spirit is not an impersonal force, but a personal reality who teaches and intercedes for believers, who possesses a mind, who can be grieved and lied to, and who is ranked as an equal partner with the Father and the Son.

In short, the New Testament church was sure that only one God existed. But they also believed that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, while personally distinct, all deserved to be called God. The challenge facing the post-apostolic church was how to make sense of these affirmations. How could the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit each be God without there being either three Gods or only one person?

Historical Background

Logos Christology

The stage for both the later Trinitarian Controversy and the Christological Controversy, in which the doctrines of the Trinity and Incarnation were forged and given creedal form, was set by the early Greek Apologists of the second century, such as Justin Martyr, Tatian, Theophilus, and Athenagoras. Connecting the divine Word (Logos) of the prologue of John’s Gospel (Jn. 1.1-5) with the divine Logos (Reason) as it played a role in the system of the Hellenistic Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria (25 BC-AD 40), the Apologists sought to explain Christian doctrine in Philonic categories. For good or for ill, their appropriation of Hellenistic thought is one of the most striking examples of the profound and enduring influence of philosophy upon Christian theology. For Philo the Logos was God’s reason, which is the creative principle behind the creation of the world and which, in turn, informs the world with its rational structure. Similarly, for the Christian Apologists, God the Father, existing alone without the world, had within Himself His Word or Reason or Wisdom (cf. Prov. 8.22-31), which somehow proceeded forth from Him, like a spoken word from a speaker’s mind, to become a distinct individual who created the world and ultimately became incarnate as Jesus Christ. The procession of the Logos from the Father was variously conceived as taking place either at the moment of creation or, alternatively, eternally. Although Christological concerns occupied center stage, the Holy Spirit, too, might be understood to proceed from God the Father’s mind. Here is how Athenagoras describes it:

The Son of God is the Word of the Father in Ideal Form and energizing power; for in his likeness and through him all things came into existence, which presupposes that the Father and the Son are one. Now since the Son is in the Father and the Father in the Son by a powerful unity of Spirit, the Son of God is the mind and reason of the Father… He is the first begotten of the Father. The term is used not because he came into existence (for God, who is eternal mind, had in himself his word or reason from the beginning, since he was eternally rational) but because he came forth to serve as Ideal Form and Energizing Power for everything material… The… Holy Spirit. . . we regard as an effluence of God which flows forth from him and returns like a ray of the sun (A Plea for the Christians 10).

According to this doctrine, then, there is one God, but He is not an undifferentiated unity. Rather certain aspects of His mind become expressed as distinct individuals. The Logos doctrine of the Apologists thus involves a fundamental reinterpretation of the Fatherhood of God: God is not merely the Father of mankind or even, especially, of Jesus of Nazareth, rather He is the Father from whom the Logos is begotten before all worlds. Christ is not merely the only-begotten Son of God in virtue of his Incarnation; rather he is begotten of the Father even in his pre-incarnate divinity.

Modalism

The Logos-doctrine of the Greek Apologists was taken up into Western theology by Irenaeus, who identifies God’s Word with the Son and His Wisdom with the Holy Spirit (Against Heresies 4.20.3; cf. 2.30.9). During the following century, a quite different conception of the divine personages emerged in contrast to the Logos doctrine. Noetus, Praxeus, and Sabellius espoused a unitarian view of God, variously called Modalism, Monarchianism, or Sabellianism, according to which the Son and Spirit are not distinct individuals from the Father. Either the Father it was who became incarnate, suffered, and died, the Son being at most the human aspect of Christ, or else the one God sequentially assumed three roles as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in relation to His creatures. In his refutation of Modalism Against Praxeas, the North African Church Father Tertullian brought greater precision to many of the ideas and much of the terminology later adopted in the creedal formulations of the doctrine of the Trinity. While anxious to preserve the divine “monarchy” (a term employed by the Greek Apologists to designate monotheism), Tertullian insisted that we dare not ignore the divine “economy” (a term borrowed from Irenaeus), by which Tertullian seems to mean the way in which the one God exists. The error of the Monarchians or Modalists is their “thinking that one cannot believe in one only God in any other way than by saying that the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are the very selfsame person.” But while “all are of one, by unity (that is) of substance,” Tertullian insists that

the mystery of the economy . . . distributes the unity into a Trinity, placing in their order the three persons—the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit: three, however, not in condition, but in degree; not in substance, but in form; not in power, but in aspect; yet of one substance, and of one condition, and of one power, inasmuch as He is one God, from whom these degrees and forms and aspects are reckoned, under the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. (Against Praxeas 2)

In saying that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are one in substance, Tertullian employs the word “substance” in both the senses explained by Aristotle. First, there is, as Tertullian affirms, just “one God,” one thing which is God. But Tertullian also means that the three distinct persons share the same essential nature. Thus, in his exegesis of the Monarchian proof-text “I and my Father are one” (Jn 10.30), Tertullian points out that the plural subject and verb intimate that there are two entities, namely, two persons, involved, but that the predicate is an abstract, not a personal, noun, unum, not unus. He comments, “Unum, a neuter term, . . . does not imply singularity of number, but unity of essence, likeness, conjunction, affection on the Father’s part, . . . and submission on the Son’s . . . . When He says, ‘I and my Father are one’ in essence—unum—He shows that there are two, whom He puts on an equality and unites in one” (22).

So when Tertullian says that the one substance is distributed into three forms or aspects, he is not affirming Modalism, but the diversity of three persons sharing the same nature. Indeed, he is so bold in affirming the distinctness of the persons, even calling them “three beings” (13; cf. 22), that he seems at times to court tri-theism. Comparing the Father and the Son to the sun and a sunbeam, he declares, “For although I make not two suns, still I shall reckon both the sun and its ray to be as much two things and two forms of one undivided substance, as God and His Word, as the Father and the Son” (13). Thus, he conceives the Son to be “really a substantive being, by having a substance of his own, in such a way that he may be regarded as an objective thing and a person, and so able . . . to make two, the Father and the Son, God and the Word” (7). Tertullian even seems to think of the Father and Son as distinct parcels of the same spiritual stuff out of which, in his idiosyncratic view, he believed God to be constituted (7).

Conventional wisdom has it that in affirming that God is three persons, Church Fathers like Tertullian meant at most three individuals, not three persons in the modern, psychological sense of three centers of self-consciousness. I shall return to this issue when we look at the creedal formulation of Trinitarian doctrine, but for now I may note that an examination of Tertullian’s statements suggests that such a claim is greatly exaggerated. In a remarkable passage aimed at illustrating the doctrine of the Son as the immanent Logos in the Father’s mind, Tertullian invites his reader, who, he says, is created in the image and likeness of God, to consider the role of reason in the reader’s own self-reflective thinking. “Observe, then, that when you are silently conversing with yourself, this very process is carried on within you by your reason, which meets you with a word at every movement of your thought, at every impulse of your conception” (5). Tertullian envisions one’s own reason as a sort of dialogue partner when one is engaged in self-reflective thought. No doubt every one of us has carried on such a dialogue with himself, which requires not merely consciousness on one’s part but self-consciousness. Tertullian’s point is that “in a certain sense, the word is a second person within you” through which you generate thought. He realizes, of course, that no human being is literally two persons, but he holds that “all this is much more fully transacted in God,” who possesses His immanent Logos even when He is silent. Or again, in proving the personal distinctness of the Father and the Son, Tertullian appeals to Scriptural passages employing first- and second-person indexical words distinguishing Father and Son. Quoting Psalm 110.3, Tertullian says to the Modalist, “If you want me to believe Him to be both the Father and the Son, show me some other passage where it is declared, ‘The Lord said unto Himself, I am my own Son, today I have begotten myself’” (11). He quotes numerous passages which, through their use of personal indexicals, illustrate the “I-Thou” relationship in which the persons of the Trinity stand to one another. He challenges the Modalist to explain how a Being who is absolutely one and singular can use first-person plural pronouns, as in “Let us make man in our image.” Tertullian clearly thinks of the Father, Son, and Spirit as individuals capable of employing first-person indexicals and addressing one another with second-person indexicals, which entails that they are self-conscious persons. Hence, “in these few quotations the distinction of persons in the Trinity is clearly set forth” (11). Tertullian thus implicitly affirms that the persons of the Trinity are three, distinct, self-conscious individuals.

The only qualification that might be made to this picture lies in a vestige of the Apologists’ Logos-doctrine in Tertullian’s theology. He not only accepts their view that there are relations of derivation among the persons of the Trinity, but that these relations are not eternal. The Father he calls “the fountain of the Godhead” (29); “the Father is the entire substance, but the Son is a derivation and portion of the whole” (9). The Father exists eternally with His immanent Logos, and at creation, before the beginning of all things, the Son proceeds from the Father and so becomes His first begotten Son, through whom the world is created (19). Thus, the Logos only becomes the Son of God when He proceeds from the Father as a substantive being (7). Tertullian is fond of analogies such as the sunbeam emitted by the sun or the river by the spring (8, 22) to illustrate the oneness of substance of the Son as He proceeds from the Father. The Son, then, is “God of God” (15). Similarly, the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father through the Son (4). It seems that Tertullian would consider the Son and Spirit to be distinct persons only after their procession from the Father (7); but it is clear that he insists on their personal distinctness from at least that point.

Through the efforts of Church Fathers like Tertullian, Hippolytus, Origen, and Novatian, the Church came to reject Modalism as a proper understanding of God and to affirm the distinctness of the three persons called Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. During the ensuing century, the Church would be confronted with a challenge from the opposite end of the spectrum: Arianism, which affirmed the personal distinctness of the Father and the Son, but only at the sacrifice of the Son’s deity.

Arianism

In 319 an Alexandrian presbyter named Arius began to propagate his doctrine that the Son was not of the same substance with the Father, but was rather created by the Father before the beginning of the world. This marked the beginning of the great Trinitarian Controversy, which lasted through the end of the century and gave us the Nicene and Constantinopolitan Creeds. Although Alexandrian theologians like Origen had argued, in contrast to Tertullian, that the begetting of the Logos from the Father did not have a beginning but is from eternity, the reason most theologians found Arius’ doctrine unacceptable was not, as he fancied, so much because he affirmed “The Son has a beginning, but God is without beginning” (Letter to Eusebius of Nicomedia 4-5). Rather what was objectionable was that Arius even denied that the Logos pre-existed immanently in God before being begotten or was in any sense from the substance of the Father, so that his beginning was not, in fact, a begetting but a creation ex nihilo and that therefore the Son is a creature. As Athanasius, Bishop of Alexandria, was later to protest, on Arius’s view God without the Son lacked His Word and His Wisdom, which is blasphemous (Orations against the Arians 1.6.17). On Arius’s view, the Son is “a creature and a work, not proper to the Father’s essence” (1.3.9). In 325 the Council of Antioch condemned anyone who says that the Son is a creature or originated or made or not truly an offspring or that once he did not exist; and later that year the ecumenical Council of Nicea issued its creedal formulation of Trinitarian belief.

The creed states,

We believe in one God, the Father All Governing, creator of all things visible and invisible;

And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, begotten of the Father as only begotten, that is, from the essence of the Father, God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten not created, of the same essence as the Father, through whom all things came into being, both in heaven and in earth; Who for us men and for our salvation came down and was incarnate, becoming human. He suffered and the third day he rose, and ascended into the heavens. And he will come to judge both the living and the dead.

And [we believe] in the Holy Spirit.

But, those who say, Once he was not, or he was not before his generation, or he came to be out of nothing, or who assert that he, the Son of God, is a different hypostasis or ousia, or that he is a creature, or changeable, or mutable, the Catholic and Apostolic Church anathematizes them.

Several features of this statement deserve comment: (1) The Son (and by implication the Holy Spirit) is declared to be of the same essence (homoousios) as the Father. This is to say that the Son and Father both exemplify the same divine nature. Therefore, the Son cannot be a creature, exemplifying, as Arius claimed, a nature different (heteroousias) from the divine nature. (2) The Son is declared to be begotten, not made. This anti-Arian affirmation is said with respect to Christ’s divine nature, not his human nature, and represents the legacy of the old Logos Christology. In the creed of Eusebius of Caesarea used as a draft of the Nicene statement, the word “Logos” stood where “Son” stands in the Nicene Creed, and the Logos is declared to be “begotten of the Father before all ages.” The condemnations appended to the Nicene Creed similarly imply that this begetting is eternal. Athanasius explains through a subtle word play that while both the Father and the Son are agenetos (that is, did not come into being at some moment), nevertheless only the Father is agennetos (that is, unbegotten), whereas the Son is gennetos (begotten ) eternally from the Father (Four Discourses against the Arians 1.9.31). (3) The condemnation of those who say that Christ “is a different hypostasis or ousia” from the Father occasioned great confusion in the Church. For Western, Latin-speaking theologians the Greek word hypostasis was etymologically parallel to and, hence, synonymous with the Latin substantia (substance). Therefore, they denied a plurality of hypostaseis in God. Although the Nicene Creed was drafted in Greek, the meaning of the terms is Western. For many Eastern, Greek-speaking theologians hypostasis and ousia were not synonymous. Ousia meant “substance,” and hypostasis designated a concrete individual, a property-bearer. As Gregory of Nyssa, one of three Cappadocian Church Fathers renowned for their explication of the Nicene Creed, explains, a hypostasis is “what subsists and is specially and peculiarly indicated by [a] name,” for example, Paul, in contrast to ousia, which refers to the universal nature common to things of a certain type, for example, man (Epistle 38.2-3). The Father and Son, while sharing the same substance, are clearly distinct hypostaseis, since they exemplify different properties (only the Father for example, has the property of being unbegotten). Therefore, the Nicene Creed’s assertion that the Father and Son are the same hypostasis sounded like Modalism to many Eastern thinkers. After decades of intense debate, this terminological confusion was cleared up at the Council of Alexandria in 362, which affirmed homoousios but allowed that there are three divine hypostaseis.

What were these hypostaseis, all exemplifying the divine nature? The unanimous answer of orthodox theologians was that they were three persons. It is customarily said, as previously mentioned, that we must not read this affirmation anachronistically, as employing the modern psychological concept of a person. This caution must, however, be qualified. While “hypostasis” does not mean “person,” nevertheless a rational hypostasis comes very close to what we mean by “person.” For Aristotle the generic essence of man is captured by the phrase “rational animal.” Animals have souls but lack rationality, and it is the property of rationality that serves to distinguish human beings from other animals. Thus, a rational hypostasis can only be what we call a person. It is noteworthy that Gregory of Nyssa’s illustration of three hypostaseis having one substance is Peter, James, and John all exemplifying the same human nature (“On Not Three Gods” to Ablabius). How else can this be taken than as an intended illustration of three persons with one nature? Moreover, the Cappadocians ascribe to the three divine hypostaseis the properties constitutive of personhood, such as mutual knowledge, love, and volition, even if, as Gregory of Nazianzus emphasizes, these are always in concord and so incapable of being severed from one another (Third Theological Oration: On the Son 2). Thus, Gregory boasts that his flock, unlike the Sabellians, “worship the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, One Godhead; God the Father, God the Son and (do not be angry) God the Holy Spirit, One Nature in Three Personalities, intellectual, perfect, self-existent, numerically separate, but not separate in Godhead” (Oration 33.16). The ascription of personal properties is especially evident in the robust defense of the full equality of the Holy Spirit with the Father and the Son as a divine hypostasis. Basil states that the Holy Spirit is not only “incorporeal, purely immaterial, and indivisible,” but that “we are compelled to direct our thoughts on high, and to think of an intelligent being, boundless in power” (On the Holy Spirit 9.22). Quoting I Cor. 2.11, he compares God’s Spirit to the human spirit in each of us (16.40) and states that in His sanctifying work the Holy Spirit makes people spiritual “by fellowship with Himself” (9.23). The Cappadocians would have resisted fiercely any attempt to treat the Holy Spirit as an impersonal, divine force. Thus, their intention was to affirm that there really are three persons in a rich psychological sense who are the one God.

In sum, while Modalism affirmed the equal deity of the three persons at the expense of their personal distinctness, orthodox Christianity maintained both the equal deity and personal distinctness of the three persons. Moreover, they did so while claiming to maintain the commitment of all parties to monotheism. There exists only one God, who is three persons, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Models of the Trinity

Does the doctrine of the Trinity make sense? Enlightenment thinkers denounced the doctrine as an incoherence; but during the twentieth century many theologians came to a reappreciation of Trinitarian theology, and in recent decades a number of Christian philosophers have sought to formulate defensible versions of the doctrine of the Trinity. Two broad models or approaches are typically identified: Social Trinitarianism, which lays greater emphasis on the diversity of the persons, and Latin Trinitarianism, which places greater stress on the unity of God. This nomenclature is, however, misleading, since the great Latin Church Fathers Tertullian and Hilary were both Social Trinitarians, as was Athanasius, a fount of Latin theology. Therefore, I shall instead contrast Social Trinitarianism with what one wag has called Anti-Social Trinitarianism. The central commitment of Social Trinitarianism is that in God there are three distinct centers of self-consciousness, each with its proper intellect and will. The central commitment of Anti-Social Trinitarianism is that there is only one God, whose unicity of intellect and will is not compromised by the diversity of persons. Social Trinitarianism threatens to veer into tri-theism; Anti-Social Trinitarianism is in danger of lapsing into unitarianism.

Social Trinitarians typically look to the Cappadocian Fathers as their champions. As we have seen, they explain the difference between substance and hypostasis as the difference between a generic essence, say, man, and particular exemplifications of it, in this case, several men like Peter, James, and John. This leads to an obvious question: if Peter, James, and John are three men each having the same nature, then why would not the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit similarly be three Gods each exemplifying the divine nature?

In his letter to Ablabius “On ‘Not Three Gods’,” Gregory of Nyssa struggled to answer this question. He emphasizes the primacy of the universal, which is one and unchangeable in each of the three men. This is merely to highlight a universal property, which Gregory holds to be one in its many exemplifications, rather than the property instance of that universal in each man. Gregory, like Plato, thinks of the universal as the primary reality. He advises that rather than speak of three Gods, we ought instead to speak of one man. But this answer solves nothing. Even if we think of the universal as the primary reality, still it is undeniable that there are three exemplifications of that reality who, in the one case, are three distinct men, as is obvious from the fact that one man can cease to exist without the others’ ceasing to do so. Similarly, even if the one divine nature is the primary reality, still it is undeniably exemplified by three hypostaseis, who should each be an instance of deity.

In order to block the inference to three Gods, Gregory also appeals to the ineffability of the divine nature and to the fact that all the operations of the Trinity toward the world involve the participation of all three persons. But even granted his assumptions, one cannot justifiably conclude that there are not three cooperatively acting individuals who each exemplify this ineffable nature, and any remaining indistinguishability seems purely epistemic, not ontological.

Gregory goes on to stress that every operation between God and creation finds its origin in the Father, proceeds through the Son, and is perfected by the Holy Spirit. Because of this, he claims, we cannot speak of those who conjointly and inseparably carry out these operations as three Gods. But Gregory’s inference seems unjustified. Simply because we creatures cannot distinguish the persons who carry out such operations, one cannot therefore conclude that there are not three instances of the divine nature at work; moreover, the very fact that these operations originate in the Father, proceed through the Son, and are perfected by the Spirit seems to prove that there are three distinct if inseparable operations in every work of the Trinity toward creation.

Finally, Gregory appears to deny that the divine nature can be multiply exemplified. He identifies the principle of individuation as “bodily appearance, and size, and place, and difference in figure and color”—”That which is not thus circumscribed is not enumerated, and that which is not enumerated cannot be contemplated in multitude.” Therefore, the divine nature “does not admit in its own case the signification of multitude.” But if this is Gregory’s argument, not only is it incompatible with there being three Gods, but it precludes there being even one God. The divine nature would be unexemplifiable, since there is no principle to individuate it. If it cannot be enumerated, there cannot even be one. On the other hand, if Gregory’s argument intends merely to show that there is just one generic divine nature, not many, then he has simply proved too little: for the universal nature may be one, but multiply exemplifiable. Given that there are three hypostaseis in the Godhead, distinguished according to Gregory by the intra-Trinitarian relations, then there should be three Gods. The most pressing task of contemporary Social Trinitarians is to find some more convincing answer to why, on their view, there are not three Gods.

Anti-Social Trinitarians typically look to Latin-speaking theologians like Augustine and Aquinas as their champions. To a considerable extent the appeal to Augustine rests on a misinterpretation which results from taking in isolation his analogies of the Trinity in the human mind, such as the lover, the beloved, and love itself (On the Trinity 8.10.14; 9.2.2) or memory, understanding, and will (or love) (10.11.17-18). Augustine explicitly states that the persons of the Trinity are not identified with these features of God’s mind; rather they are “an image of the Trinity in man” (14.8.11; 15.8.14). “Do we,” he asks, “in such manner also see the Trinity that is in God?” He answers, “Doubtless we either do not at all understand and behold the invisible things of God by those things that are made, or if we behold them at all, we do not behold the Trinity in them” (15.7.10). In particular Augustine realizes that these features are not each identical to a person but rather are features which any single human person possesses (15.7.11). Identifying the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit with the divine memory, understanding, and love would, Augustine recognizes, lead to the absurd conclusion that the Father knows Himself only by the Son or loves Himself only by the Holy Spirit, as though the Son were the understanding of the Father and the Spirit and the Father the memory of the Spirit and the Son! Rather memory, understanding, and will (or love) must belong to each of the persons alone (15.7.12). Augustine concludes with the reflection that having found in one human person an image of the Trinity, he had desired to illuminate the relation among the three divine persons; but in the end three things which belong to one person cannot suit the three persons of the Trinity (15.24.45).

Anti-Social Trinitarians frequently interpret Augustine to hold that the persons of the Trinity just are various relations subsisting in God. But this is not what Augustine says (5.3.4 - 5.5.6). Arians had objected that if the Father is essentially unbegotten and the Son essentially begotten, then the Father and Son cannot share the same essence or substance (homoousios). In response to this ingenious objection Augustine claims that the distinction between Father and Son is a matter neither of different essential properties nor of different accidental properties. Rather the persons are distinguished in virtue of the relations in which they stand. Because “Father” and “Son” are relational terms implying the existence of something else, Augustine thinks that properties like begotten by God cannot belong to anything’s essence. He evidently assumes that only intrinsic properties go to constitute something’s essence. But if being begotten is not part of the Son’s essence, is it not accidental to Him? No, says Augustine, for it is eternally and immutably the case for the Son to be begotten. Augustine’s answer is not adequate, however, since eternality and immutability are not sufficient for necessity; there could still be possible worlds in which the person who in the actual world is the Father does not beget a Son and so is not a Father. Augustine should instead claim that “Father” and “Son” imply internal relations between the persons of the Godhead, so that there is no possible world in which they do not stand in that relation. The Father and Son would share the same intrinsic essential properties, but they would differ in virtue of their differing relational properties or the different internal relations in which they stand. Note what Augustine does not say, namely, that the Father and Son just are relations. It is true that Augustine felt uneasy about the terminology of “three persons” because this seems to imply three instances of a generic type and, hence, three Gods (5.9.10; 7.4.7-8). He accepted the terminology somewhat grudgingly for want of a better word. But he did not try to reduce the persons to mere relations.

For a bonafide example of Anti-Social Trinitarianism, we may turn to Thomas Aquinas, who pushes the Augustinian analogy to its apparent limit. Aquinas holds that there is a likeness of the Trinity in the human mind insofar as it understands itself and loves itself (Summa contra gentiles 4.26.6). We find in the mind the mind itself, the mind conceived in the intellect, and the mind beloved in the will. The difference between this human likeness and the Trinity is, first, that the human mind’s acts of understanding and will are not identical with its being and, second, that the mind as understood and the mind as beloved do not subsist and so are not persons. By contrast, Aquinas’ doctrine of divine simplicity implies that God’s acts of understanding and willing are identical with His being, and he further holds (paradoxically) that God as understood and God as beloved do subsist and therefore count as distinct persons from God the Father. According to Aquinas, since God knows Himself, there is in God the one who knows and the intentional object of that knowledge, which is the one known. The one known exists in the one knowing as His Word. They share the same essence and are, indeed, identical to it, but they are relationally distinct (4.11.13). Indeed, Aquinas holds that the different divine persons just are the different relations in God, like paternity (being father of)and filiation (being son of) (Summa theologiae 1a.40.2). Despite his commitment to divine simplicity, Aquinas regards these relations as subsisting entities in God (Scg 4.14.6, 11). Because the one knowing generates the one known and they share the same essence, they are related as Father to Son. Moreover, God loves Himself, so that God as beloved is relationally distinct from God as loving (4.19.7-12) and is called the Holy Spirit. Since God’s knowing and willing are not really distinct, the Son and Holy Spirit would be one person if the only difference between them were that one proceeds by way of God’s knowing Himself and the other by way of God’s loving Himself. But they are distinct because only the Holy Spirit proceeds from both the Father and the Son.

Assessment of the Models

Anti-Social Trinitarianism

Is Thomistic Anti-Social Trinitarianism viable? Thomas’ doctrine of the Trinity is doubtless inconsistent with his doctrine of divine simplicity. Intuitively, it seems obvious that a being which is absolutely without composition and transcends all distinctions cannot have real relations subsisting within it, much less be three distinct persons. More specifically, Aquinas’ contention that each of the three persons has the same divine essence entails, given divine simplicity, that each person just is that essence. But if two things are identical with some third thing, they are identical with each other. Therefore, the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit cannot be distinct persons or relations. Since this unwelcome conclusion arises, not so much from Aquinas’ Trinitarian doctrine, as from the doctrine of divine simplicity, and since we have already found reason to call that doctrine seriously into question, let us ask whether Thomas’ account of Anti-Social Trinitarianism is viable once freed of the constraints of the simplicity doctrine.

It seems not. Without begging the question in favor of Social Trinitarianism, it can safely be said that on no reasonable understanding of “person” can a person be equated with a relation. Relations do not cause things, know truths, or love people in the way the Bible says God does. Moreover, to think that the intentional objects of God’s knowing Himself and loving Himself constitute in any sense really distinct persons is wholly implausible. Even if God the Father were a person, and not a mere relation, there is no reason, even in Aquinas’ own metaphysical system, why the Father as understood and loved by Himself would be different persons. The distinction involved here is merely that between oneself as subject (“I”) and as object (“me”). There is no more reason to think that the individual designated by “I”, “me”, and “myself” constitute a plurality of persons in God’s case than in any human being’s case. Anti-Social Trinitarianism seems to reduce to classical Modalism.

Suppose the Anti-Social Trinitarian insists that in God’s case, the subsistent relations within God really do constitute distinct persons in a sufficiently robust sense. Then two problems present themselves. First, there arises an infinite regress of persons in the Godhead. If God as understood really is a distinct person, called the Son, then the Son, like the Father, must also understand Himself and love Himself. There are thereby generated two further persons of the Godhead, who, in turn, can also consider themselves as intentional objects of their knowledge and will, thereby generating further persons, ad infinitum. We wind up with a fractal-like infinite series of Trinities within Trinities in the Godhead. Aquinas actually considers this objection, and his answer is that “just as the Word is not another god, so neither is He another intellect; consequently, not another act of understanding; hence, not another word (Scg 4.13.2). This answer only reinforces the previous impression of Modalism, for the Son’s intellect and act of understanding just are the Father’s intellect and act of understanding; the Son’s understanding Himself is identical with the Father’s understanding Himself. The Son seems but a name given to the Father’s “me.” Second, one person does not exist in another person. On Aquinas’ view the Son or Word remains in the Father (4.11.180). While we can make sense of a relation’s existing in a person, it seems unintelligible to say that one person exists in another person. (Two persons’ inhabiting the same body is obviously not a counter-example.) Classic Trinitarian doctrine affirms that more than one person may exist in one being, but persons are not the sort of entity that exists in another person. It is true that the classic doctrine involves a perichoreisis (circumcessio) or mutual indwelling of the three persons in one another which is often enunciated as each person’s existing in the others. But this may be understood in terms of complete harmony of will and action, of mutual love, and full knowledge of one another with respect to the persons of the Godhead; beyond that it remains obscure what could be literally meant by one person’s being in another person. Again, we seem forced to conclude that the subsisting relations posited by the Anti-Social Trinitarian do not rise to the standard of personhood.

Social Trinitarianism

Are there brighter prospects for a viable Social Trinitarianism? Brian Leftow has distinguished three forms of Social Trinitarianism on offer: Trinity Monotheism, Group Mind Monotheism, and Functional Monotheism.

To consider these in reverse order, Functional Monotheism appeals to the harmonious, interrelated functioning of the divine persons as the basis for viewing them as one God. For example, Richard Swinburne considers God to be a logically indivisible, collective substance composed of three persons who are also substances. He sees the Father as the everlasting active cause of the Son and Spirit, and the latter as permissive causes, in turn, of the Father. Because all of them are omnipotent and perfectly good, they cooperate in all their volitions and actions. It is logically impossible that any one person should exist or act independently of the other two. Swinburne considers this understanding sufficient to capture the intention of the Church Councils, whose monotheistic affirmations, he thinks, meant to deny that there were three independent divine beings who could exist and act without one another.

Leftow blasts Swinburne’s view as “a refined paganism,” a thinly veiled form of polytheism. [3] Since, on Swinburne’s view, each person is a discrete substance, it is a distinct being, even if that being is causally dependent upon some other being for its existence. Indeed, the causal dependence of the Son on the Father is problematic for the Son’s being divine. For on Swinburne’s account, the Son exists in the same way that creatures exist—only due to a divine person’s conserving Him in being and not annihilating Him. Indeed, given that the Son is a distinct substance from the Father, the Father’s begetting the Son amounts to creatio ex nihilo, which as Arius saw, makes the Son a creature. If we eliminate from Swinburne’s account the causal dependence relation among the divine persons, then we are stuck with the surprising and inexplicable fact that there just happen to exist three divine beings all sharing the same nature, which seems incredible. As for the unity of will among the three divine persons, there is no reason at all to see this as constitutive of a collective substance, for three separate Gods who were each omnipotent and morally perfect would similarly act cooperatively, if Swinburne’s argument against the possibility of dissension is correct. Thus, there is no salient difference between Functional Monotheism and polytheism.

Group Mind Monotheism holds that the Trinity is a mind which is composed of the minds of the three persons in the Godhead. If such a model is to be theologically acceptable, the mind of the Trinity cannot be a self-conscious self in addition to the three self-conscious selves who are the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, for otherwise we have not a Trinity but a Quaternity, so to speak. Therefore, the Trinity cannot itself be construed as an agent, endowed with intellect and will, in addition to the three persons of the Trinity. The three persons would have to be thought of as subminds of the mind of God. In order to motivate such a view, Leftow appeals to thought experiments involving surgical operations in which the cerebral commissures, the network of nerves connecting the two hemispheres of the brain, are severed. Such operations have been performed as a treatment for severe epilepsy, and the results are provocative. Patients sometimes behave as though the two halves of their brain were operating independently of each other. The interpretation of such results is controversial, but one interpretation, suggested by various thought experiments, is that the patients come to have two minds. Now the question arises whether in a normally functioning human being we do not already have two separable subminds linked to their respective hemispheres which cooperate together in producing a single human consciousness. In such a case the human mind would itself be a group mind.

Applying this notion of a group mind to the Trinity, we must, if we are to remain biblically orthodox, maintain that the minds of the persons of the Trinity are more than mere subminds which either never come to self-consciousness or else share a common mental state as a single self-consciousness. For such a view is incompatible with the persons’ existing in an “I-Thou” relationship with one another; on such a view there really is only one person which God is.

In order to be theologically acceptable, Group Mind Monotheism will have to be construed dynamically, as a process in which the subminds emerge into self-consciousness to replace the single Trinitarian self-consciousness. In other words, what Group Mind Monotheism offers is a strikingly modern version of the old Logos doctrine of the Greek Apologists. The divine Monarchy (the single self-consciousness of the Trinity) contains within itself an immanent Logos (a submind) which at the beginning of the creation of the world is deployed into the divine Economy (the subminds emerge into self-consciousness in replacement of the former single self-consciousness).

This provocative model gives some sense to the otherwise very difficult idea of the Father’s begetting the Son in His divine nature. On the other hand, if we think of the primal self-consciousness of the Godhead as the Father, then the model requires that the person of the Father expires in the emergence of the three subminds into self-consciousness (cf. Athanasius Four Discourses against the Arians 4.3). In order to avoid this unwelcome implication, one would need to think of some way in which the Father’s personal identity is preserved through the deployment of the divine economy, just as a patient survives a commissurotomy.

The whole model depends, of course, upon the very controversial notion of subminds and their emergence into distinct persons. If we do not equate minds with persons, then the result of the deployment of the divine economy will be merely one person with three minds, which falls short of the doctrine of the Trinity. But if, as seems plausible, we understand minds and persons to exist in a one-to-one correspondence, then the emergence of three distinct persons raises once again the specter of tri-theism. The driving force behind Group Mind Monotheism was to preserve the unity of God’s being in a way Functional Monotheism could not. But once the divine economy has been deployed, the group mind has lapsed away, and it is unclear why we do not now have three Gods in the place of one.

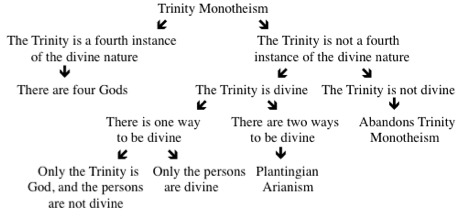

We turn finally to Trinity Monotheism, which holds that while the persons of the Trinity are divine, it is the Trinity as a whole which is properly God. If this view is to be orthodox, it must hold that the Trinity alone is God and that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, while divine, are not Gods. Leftow presents the following challenge to this view:

Either the Trinity is a fourth case of the divine nature, in addition to the Persons, or it is not. If it is, we have too many cases of deity for orthodoxy. If it is not, and yet is divine, there are two ways to be divine—by being a case of deity, and by being a Trinity of such cases. If there is more than one way to be divine, Trinity monotheism becomes Plantingian Arianism. But if there is in fact only one way to be divine, then there are two alternatives. One is that only the Trinity is God, and God is composed of non-divine persons. The other is that the sum of all divine persons is somehow not divine. To accept this last claim would be to give up Trinity monotheism altogether. [4]

Leftow’s dilemma may be graphically exhibited as follows:

How should the Trinity Monotheist respond to this dilemma? Starting with the first disjunction, he will clearly want to say that the Trinity is not a fourth instance of the divine nature, lest there be four divine persons. Moving then to the next set of options, he must say that the Trinity is divine, since that is entailed by Trinity Monotheism. Now if the Trinity is divine but is not a fourth instance of the divine nature, this suggests that there is more than one way to be divine. This alternative is said to lead to Plantingian Arianism. What is that? Leftow defines it as “the positing of more than one way to be divine.” [5] This is uninformative, however; what we want to know is why the view is objectionable. Leftow responds, “If we take the Trinity’s claim to be God seriously, . . . we wind up downgrading the Persons’ deity and/or [being] unorthodox.” [6] The alleged problem is that if only the Trinity exemplifies the complete divine nature, then the way in which the persons are divine is less than fully divine.

This inference would follow, however, only if there were but one way to be divine (namely, by exemplifying the divine nature); but the position asserts that there is more than one way to be divine. The persons of the Trinity are not divine in virtue of exemplifying the divine nature. For presumably being triune is a property of the divine nature (God does not just happen to be triune); yet the persons of the Trinity do not exemplify that property. It now becomes clear that the reason that the Trinity is not a fourth instance of the divine nature is that there are no other instances of the divine nature. The Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are not instances of the divine nature, and that is why there are not three Gods. The Trinity is the sole instance of the divine nature, and therefore there is but one God. So while the statement “The Trinity is God” is an identity statement, statements about the persons like “The Father is God” are not identity statements. Rather they perform other functions, such as ascribing a title or office to a person (like “Belshazzar is King,” which is not incompatible with there being co-regents) or ascribing a property to a person (a way of saying, “The Father is divine,” as one might say, “Belshazzar is regal”).

So if the persons of the Trinity are not divine in virtue of being instances of the divine nature, in virtue of what are they divine? Consider an analogy. One way of being feline is to exemplify the nature of a cat. But there are other ways to be feline as well. A cat’s DNA or skeleton is feline, even if neither is a cat. Nor is this a sort of downgraded or attenuated felinity: a cat’s skeleton is fully and unambiguously feline. Indeed, a cat just is a feline animal, as a cat’s skeleton is a feline skeleton. Now if a cat is feline in virtue of being an instance of the cat nature, in virtue of what is a cat’s DNA or skeleton feline? One plausible answer is that they are parts of a cat. This suggests that we could think of the persons of the Trinity as divine because they are parts of the Trinity, that is, parts of God. Now obviously, the persons are not parts of God in the sense in which a skeleton is part of a cat; but given that the Father, for example, is not the whole Godhead, it seems undeniable that there is some sort of part/whole relation obtaining between the persons of the Trinity and the entire Godhead.

Far from downgrading the divinity of the persons, such an account can be very illuminating of their contribution to the divine nature. For parts can possess properties which the whole does not, and the whole can have a property because some part has it. Thus, when we ascribe omniscience and omnipotence to God, we are not making the Trinity a fourth person or agent; rather God has these properties because the persons do. Divine attributes like omniscience, omnipotence, and goodness are grounded in the persons’ possessing these properties, while divine attributes like necessity, aseity, and eternity are not so grounded. With respect to the latter, the persons have these properties because God as a whole has them. For parts can have some properties in virtue of the wholes of which they are parts. The point is that if we think of the divinity of the persons in terms of a part/whole relation to the Trinity that God is, then their deity seems in no way diminished because they are not instances of the divine nature.

Is such a solution unorthodox? It is true that the Church Fathers frequently insisted that the expression “from the substance of the Father” should not be understood to imply that the Son is formed by division or separation of the Father’s substance. But the concern here was pretty clearly to avoid imagining the divine substance as a sort of “stuff” which could be parceled out into smaller pieces. Such a stricture is wholly compatible with our suggestion that any one person is not identical to the whole Trinity, for the part/whole relation at issue here does not involve separable parts. It is simply to say that the Father, for example, is not the whole Godhead. The Latin Church Father Hilary seems to capture the idea nicely when he asserts, “Each divine person is in the Unity, yet no person is the one God” (On the Trinity 7.2; cf. 7.13, 32).

On the other hand, it must be admitted that a number of post-Nicene creeds, probably under the influence of the doctrine of divine simplicity, do include statements which can be construed to identify each person of the Trinity with God as a whole. For example, the Eleventh Council of Toledo (675) affirms, “Each single person is wholly God in Himself,” the so-called Athanasian Creed (eighth century) enjoins Christians “to acknowledge every Person by Himself to be God and Lord,” and the Fourth Lateran Council, in condemning the idea of a divine Quaternity, declares, “each of the Persons is that reality, viz., that divine substance, essence, or nature. . . . what the Father is, this very same reality is also the Son, this the Holy Spirit.” If these declarations are intended to imply that statements like “The Father is God” are identity statements, then they threaten the doctrine of the Trinity with logical incoherence. For the logic of identity requires that if the Father is identical with God and the Son is identical with God, then the Father is identical with the Son, which the same Councils also deny.

Peter van Inwagen has sought to defend the coherence of such creedal affirmations by appeal to Relative Identity. According to this notion, the identity relation is not absolute but is relative to a sort of thing. For example, we say, “The couch is the same color as the chair” (not “The couch is the chair”) or “The Lord Mayor John is the same person as the schoolboy Johnny”, (not “The Lord Mayor is the schoolboy Johnny”). Van Inwagen shows that given certain assumptions, we can coherently affirm not only statements like “The Father is the same being as the Son,” “The Father is not the same person as the Son,” but even paradoxical statements like “God is a person,” “God is the same person as the Father,” “God is the same person as the Son,” and “The Son is not the same person as the Father.” The fundamental problem with the appeal to Relative Identity, however, is that the very notion of Relative Identity is widely recognized to be spurious. Van Inwagen himself admits that apart from Trinitarian theology, there are no known cases of allegedly relative identities which cannot be analyzed in terms of classical identity. Our example of the couch and the chair is not any kind of identity statement at all, for neither piece of furniture literally is a color; rather they have the identical color as a property. The example of the Lord Mayor is solved by taking seriously the tense of the sentence; we should say, “The Lord Mayor was the schoolboy Johnny.” Not only are the alleged cases of relative identity spurious, but there is a powerful theoretical argument against making identity relative. Suppose that two things x and y could be the same N but not be the same P. In such a case x could not fail to be the same P as x itself, but y could. Therefore, x and y are discernible and so cannot be the same thing. But then it follows that they cannot be the same N, since they cannot be the same anything. Identity must therefore be absolute. Finally, even granted Relative Identity, its application to Trinitarian doctrine involves highly dubious assumptions. For example, it must be presupposed that x and y can be the identical being without being the identical person. Notice how different this is from saying that x and y are parts of the same being but are different persons. The latter statement is like the affirmation that x and y are parts of the same body but are different hands; the former is like the affirmation that x and y are the identical body but are different hands. Van Inwagen confesses that he has no answer to the questions of how x and y can be the same being without being the same person or, more generally, how x and y can be the same N without being the same P. It seems, then, that the ability to state coherently the Trinitarian claims under discussion using the device of Relative Identity is a hollow victory.

Protestants bring all doctrinal statements, even Conciliar creeds, especially creeds of non-ecumenical Councils, before the bar of Scripture. Nothing in Scripture warrants us in thinking that God is simple and that each person of the Trinity is identical to the whole Trinity. Nothing in Scripture prohibits us from maintaining that the three persons of the Godhead stand in some sort of part/whole relation to the Trinity. Therefore, Trinity Monotheism cannot be condemned as unorthodox in a biblical sense. Trinity Monotheism seems therefore to be thus far vindicated.

All of this still leaves us wondering, however, how three persons could be parts of the same being, rather than be three separate beings. What is the salient difference between three divine persons who are each a being and three divine persons who are together one being?

Perhaps we can get a start at this question by means of an analogy. (There is no reason to think that there must be any analogy to the Trinity among created things, but analogies may prove helpful as a springboard for philosophical reflection and formulation.) In Greco-Roman mythology there is said to stand guarding the gates of Hades a three-headed dog named Cerberus. We may suppose that Cerberus has three brains and therefore three distinct states of consciousness of whatever it is like to be a dog. Therefore, Cerberus, while a sentient being, does not have a unified consciousness. He has three consciousnesses. We could even assign proper names to each of them: Rover, Bowser, and Spike. These centers of consciousness are entirely discrete and might well come into conflict with one another. Still, in order for Cerberus to be biologically viable, not to mention in order to function effectively as a guard dog, there must be a considerable degree of cooperation among Rover, Bowser, and Spike. Despite the diversity of his mental states, Cerberus is clearly one dog. He is a single biological organism exemplifying a canine nature. Rover, Bowser, and Spike may be said to be canine, too, though they are not three dogs, but parts of the one dog Cerberus. If Hercules were attempting to enter Hades, and Spike snarled at him or bit his leg, he might well report, “Cerberus snarled at me” or “Cerberus attacked me.” Although the Church Fathers rejected analogies like Cerberus, once we give up divine simplicity Cerberus does seem to represent what Augustine called an image of the Trinity among creatures.

We can enhance the Cerberus story by investing him with rationality and self-consciousness. In that case Rover, Bowser, and Spike are plausibly personal agents and Cerberus a tri-personal being. Now if we were asked what makes Cerberus a single being despite his multiple minds, we should doubtless reply that it is because he has a single physical body. But suppose Cerberus were to be killed, and his minds survive the death of his body. In what sense would they still be one being? How would they differ intrinsically from three exactly similar minds which have always been unembodied? Since the divine persons are, prior to the Incarnation, three unembodied Minds, in virtue of what are they one being rather than three individual beings?

The question of what makes several parts constitute a single object rather than distinct objects is a difficult one. But in this case perhaps we can get some insight by reflecting on the nature of the soul. Souls are immaterial substances, and some substance dualists believe that animals have souls. Souls thus come in a spectrum of varying capacities and faculties. Higher animals such as chimpanzees and dolphins possess souls more richly endowed with powers than those of iguanas and turtles. What makes the human soul a person is that the human soul is equipped with rational faculties of intellect and volition which enable it to be a self-reflective agent capable of self-determination. Now God is very much like an unembodied soul; indeed, as a mental substance God just seems to be a soul. We naturally equate a rational soul with a person, since the human souls with which we are acquainted are persons. But the reason human souls are individual persons is because each soul is equipped with one set of rational faculties sufficient for being a person. Suppose, then, that God is a soul which is endowed with three complete sets of rational cognitive faculties, each sufficient for personhood. Then God, though one soul, would not be one person but three, for God would have three centers of self-consciousness, intentionality, and volition, as Social Trinitarians maintain. God would clearly not be three discrete souls because the cognitive faculties in question are all faculties belonging to just one soul, one immaterial substance. God would therefore be one being which supports three persons, just as our individual beings each support one person. Such a model of Trinity Monotheism seems to give a clear sense to the classical formula “three persons in one substance.”

Finally, such a model does not feature (though it does not preclude) the derivation of one person from another, enshrined in the confession that the Son is “begotten of the Father before all worlds, Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten, not made” (Constantinopolitan Creed). God could simply exist eternally with His multiple cognitive faculties and capacities. This is, in my opinion, all for the better. For although credally affirmed, the doctrine of the generation of the Son (and the procession of the Spirit) is a relic of Logos Christology which finds virtually no warrant in the biblical text and introduces a subordinationism into the Godhead which anyone who affirms the full deity of Christ ought to find very troubling.

Biblically speaking, the vast majority of contemporary New Testament scholars recognize that even if the word traditionally translated “only-begotten” (monogenes) carries a connotation of derivation when used in familial contexts--as opposed to meaning merely “unique” or “one of a kind” as many scholars maintain [7] -nevertheless the biblical references to Christ as monogenes (Jn 1.1, 14, 18; cf. Rev 9.13)do not contemplatesome pre-creation or eternal procession of the divine Son from the Father, but have to do with the historical Jesus’ being God’s special Son (Mt. 1.21-23; Lk. 1-35; Jn. 1.14, 34; Gal. 4.4; Heb. 1.5-6). [8] In other words, Christ’s status of being monogenes has less to do with the Trinity than with the Incarnation. This primitive understanding of Christ’s being begotten is still evident in Ignatius’s description of Christ as “one Physician, of flesh and of spirit, begotten and unbegotten, . . . both of Mary and of God” (Ephesians 7). There is here no idea that Christ in his divine nature is begotten. Indeed, the transference by the Apologists of Christ’s Sonship from Jesus of Nazareth to the pre-incarnate Logos has helped to depreciate the importance of the historical Jesus for Christian faith.

Theologically speaking, orthodox theology has stoutly rejected any depreciation of the Son vis á vis the Father. Athanasius writes sternly, “They that depreciate the Only-Begotten Son of God blaspheme God, defaming His perfection and accusing Him of imperfection, and render themselves liable to the severest chastisement” (In illud omnia mihi tradia sunt 6). The target here was subordinationism, a doctrine inspired by Neo-Platonic and Gnostic metaphysics, according the which ultimate reality, or the One, could have no intercourse with the world and thus spawned a descending series of intermediate beings which, falling away from the perfection of the One, served as mediators between it and the world. Origen, trained under the Neo-platonist philosopher Ammonius Saccas, had dared to speak of the Son as a deity of the second rank, having a sort of derivative divinity as far removed from that of the Father as He Himself is from creatures. Subsequent Church Fathers flatly rejected any suggestion that the Son was in any respect inferior to the Father, insisting that He shares the same substance or essence with the Father. Nevertheless, these same theologians continued to affirm the generation of the Son from the Father. The Son in their view derives his being from the Father. Athanasius quotes approvingly Dionysius’s affirmation that “the Son has His being not of Himself but of the Father” (On the Opinion of Dionysius 15). Similarly, Hilary declares that “He is not the source of His own being. . . . it is from His [the Father’s] abiding nature that the Son draws His existence through birth” (On the Trinity 9.53; 6.14; cf. 4.9). This doctrine of the generation of the Logos from the Father cannot, despite assurances to the contrary, but diminish the status of the Son because He becomes an effect contingent upon the Father. Even if this eternal procession takes place necessarily and apart from the Father’s will, the Son is less than the Father because the Father alone exists a se, whereas the Son exists through another (ab alio).

It is interesting to note that the Church Fathers interpreted the Arian proof-text, “The Father is greater than I” (Jn 14. 28), not in terms of Christ’s humanity, but as an expression of his being generated from the Father (Athanasius Four Discourses against the Arians 1.13.58). Hilary admits: “The Father is greater than the Son: for manifestly He is greater Who makes another to be all that He Himself is, Who imparts to the Son by the mystery of the birth the image of His own unbegotten nature, Who begets Him from Himself into His own form” (On the Trinity 9.54). But then is the Son not inferior to the Father? Hilary denies it: “The Father therefore is greater, because He is Father: but the Son, because He is Son, is not less” (9.56). This is to talk logical nonsense. It is like saying that six is greater than four, but four is not less than six. Basil, who sees the contradiction, would elude it by saying, “the evident solution is that the Greater refers to origination, while the Equal belongs to the Nature” (Fourth Theological Oration 9). This reply raises all sorts of difficult questions. Does it not belong to the nature of the Father as an individual person to be unbegotten and to the nature of the Son to be begotten? Is there a possible world in which the person who is in fact the Father is instead begotten and so in that world is the Son? Classical Trinitarian theology denies this. But then how are the Father and the Son equal in nature, if greatness refers to origination and manner of origination belongs to each individual’s nature? And even if the Father and the Son are equal in nature, why does the accidental property of being unbegotten, which inheres in the person of the Father alone, not make Him greater than the Son, since it is admittedly a great-making property or perfection? If the Father is greater than the Son in any respect, not just in nature, then the Son is in that respect inferior to the Father. At the end of the day Basil must deny that having existence a se is not, after all, a perfection or great-making property. He asserts, “That which is from such a Cause is not inferior to that which has no Cause; for it would share the glory of the Unoriginate, because it is from the Unoriginate” (Ibid.) This claim is unconvincing, however, for to be dependent upon the Unoriginate for one’s existence is to lack a ground of being in oneself alone, which is surely less great than being able to exist on one’s own. Such derivative being is, as Leftow says, the same way in which created things exist. Despite its protestations to the contrary, Nicene orthodoxy does not seem to have completely exorcised the spirit of subordinationism introduced into Christology by the Greek Apologists.

If, then, we decide to drop from our doctrine of the Trinity the eternal procession of the Son and Spirit from the Father, how should we construe the intra-Trinitarian relations? Here it will be useful to distinguish between the ontological Trinity and the economic Trinity. The ontological Trinity is the Trinity as it exists of itself apart from God’s relation to the created order. The economic Trinity has reference to the different roles played by the persons of the Trinity in relation to the world and especially in the plan of salvation. The question raised by this distinction is the degree to which the economic Trinity reflects the ontological Trinity.

Marcellus of Ancyra, one of the leaders at Nicea, noticed that in John’s Gospel the Logos is not referred to as “Son” until after the incarnation. Indeed, nowhere in the New Testament is Christ unambiguously referred to as “Son” in his pre-incarnate state (I Jn 4.14 is sometimes suggested, but even it may be read naturally in light of the Incarnation). Moreover, he found no biblical grounds for affirming the eternal generation of the Logos from the Father. These observations led Marcellus to hypothesize that prior to creation, the economic Trinity did not exist. The Logos becomes the Son only with his Incarnation. On Marcellus’s view distinctions present in the economic Trinity need not always reflect distinctions in the ontological Trinity.

Similarly, on the view presented here, the persons of the ontological Trinity can be as similar to one another as three distinct persons can be, knowing, willing, and loving the same things (though each from a different personal angle, so to speak), so that it may well be arbitrary which person plays the role of “Father” and which of “Son.” These titles have reference to the economic Trinity, to the roles played by the three persons in the plan of salvation with respect to the created order. The Son is whichever person becomes incarnate, the Spirit is He who stands in the place of and continues the ministry of the Son, and the Father is the one who sends the Son and Spirit. In a possible world in which God did not choose to create but remained alone, the economic Trinity would not exist, even though the ontological Trinity would. In the actual world the economic Trinity exists eternally, since the persons of the Godhead all know the respective roles they will play in God’s eternal plan of salvation, even if the deployment of that economy does not occur until the fullness of time.

Although they did not share Marcellus’s maverick view, both Athanasius and other members of the Nicene party continued to support him. Unfortunately, Marcellus went too far in also reverting to the view that the second and third persons of the ontological Trinity existed only in potentiality in God prior to creation, a view which, ironically, reintroduces the subordinationism that Marcellus wanted to avoid. But because I have not appealed to the intra-Trinitarian relations to ground the distinctness of the persons of the Trinity, there is no danger of lapsing with Marcellus into a sort of primordial Unitarianism. The one spiritual being which is God possesses three distinct sets of cognitive faculties each sufficient for self-consciousness, intentionality, and volition, and so for personhood, wholly apart from the intra-Trinitarian relations. Indeed, it seems doubtful that mere relations could in any case serve as the basis for the ontological distinctness of the persons. For one person can relate to himself, for example, as knower/known or lover/beloved. In order for these relations to exist between two persons, the persons must exist as distinct individuals logically (if not chronologically) prior to their standing in said relations. In other words, the persons’ distinct existence is explanatorily prior to the relations in which they stand, not vice versa. It might be said that in the special case of the father/son relation, no one person could stand in such a relation to himself, so that such a relation is sufficient to distinguish ontologically persons in the Trinity. But this is not in fact true. One of the most popular thought experiments in connection with time travel concerns a scenario in which the time traveler goes back in time, marries his mother, and begets himself, so that he turns out to be his own father! A father/son relation between two persons thus presupposes the logically prior individuality of the persons involved. Since entities which stand in a relation seem to be explanatorily prior to the relations in which they stand, intra-Trinitarian relations already presuppose a plurality of persons in the Godhead, which must be grounded in some other way, such as we have proposed.

Athanasius does consider the view that the Logos became the Son in virtue of his union with the flesh (Four Discourses against the Arians 4.20-22). In response to those who say that the Logos and the flesh together are the Son, Athanasius replies that either the Logos became the Son because of the flesh or else the flesh became the Son because of the Logos. In either case, he says, it will be either the Logos or the flesh, not their union, which really is the Son. But he notes that his opponents might escape his dilemma by holding that the Son is constituted by the concurrence of the two, so that neither in isolation can be called the Son. Athanasius’s objection to this plausible solution is that then the cause of the union of the Logos and the flesh is the true Son. But Athanasius’s objection does not seem to follow. If water is formed by the union of hydrogen and oxygen, it is not the cause of their union which is water. Similarly, the Son is the result, not the cause, of the union of the Logos with the flesh. Athanasius notes another option that his opponents might advocate: that the Son is the Son in name only. This seems even more plausible: the Son is not a new substance formed by the union of the Logos with the flesh, rather “Son” designates an office or role which the Logos enters into in virtue of the Incarnation, just as someone becomes President in virtue of being elected to that office. Athanasius objects that then the flesh is the cause of his being the Son. But that does not follow; rather it is the union of Logos and flesh together that put the Logos into the role of the Son in God’s economy.

In this economic Trinity there is subordination (or, perhaps better, submission) of one person to another, as the incarnate Son does the Father’s will and the Spirit speaks, not on His own account, but on behalf of the Son. The economic Trinity does not reflect ontological differences between the persons but rather is an expression of God’s loving condescension for the sake of our salvation. The error of Logos Christology lay in conflating the economic Trinity with the ontological Trinity, introducing subordination into the nature of the Godhead itself.