God and Cosmology: The Existence of God in Light of Contemporary Cosmology

September 2015William Lane Craig vs. Sean Carroll

New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, New Orleans, LA - March 2014

Dr. Stewart, Moderator - Introduction

We are glad to see all of you here this evening, and all of those who are watching online as well. . . . Let me introduce our speakers, as if you don’t know who they are already!

William Lane Craig is a Research Professor of Philosophy at Talbot School of Theology in La Mirada, California, and a Professor of Philosophy at Houston Baptist University. He earned a doctorate in philosophy at the University of Birmingham, England, before taking a doctorate in theology from the University of Munich, Germany, where he was, for two years, a Fellow of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. Prior to his appointment at Talbot he spent seven years at the Higher Institute of Philosophy of the Katholike Universiteit Leuven, Belgium. His research interests include the interface of philosophy of religion and philosophy of space and time. He has authored or edited over 30 books including The Kalam Cosmological Argument; Theism, Atheism, and Big Bang Cosmology; and Time and the Metaphysics of Relativity. He has published over 150 articles in peer reviewed professional journals, such as The Journal of Philosophy, British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, International Studies in the Philosophy of Science, Philosophia Naturalis, and Astrophysics and Space Science. He has appeared as a guest on television shows such as 20/20, CNN Newsroom, Fox News, and Closer to the Truth.

Sean Carroll is a physicist and Senior Research Associate in the Department of Physics at the California Institute of Technology. He received his PhD in astronomy and astrophysics from Harvard University. His research focus is on theoretical physics and cosmology, especially the origin and constituents of the universe. He has contributed to models of interactions between dark matter, dark energy, and ordinary matter, alternative theories of gravity, and the arrow of time. Carroll is the author of From Eternity to Here: The Quest for the Ultimate Theory of Time, Spacetime and Geometry: An Introduction to General Relativity, and The Particle at the End of the Universe. He has been awarded fellowships by the Sloan Foundation, Packard Foundation, and the American Physical Society, and won the 2013 Royal Society Winton Prize for Science Books. He has appeared on TV shows such as the Colbert Report, Through the Wormhole with Morgan Freeman, and Closer to Truth.

Welcome our guests as they come to speak to us!

Dr. Craig - Opening Speech

Good evening! It is an honor to be taking part in a forum featuring such distinguished scientists and philosophers. Thank you very much!

Introductory Remarks

In his recent book, Where the Conflict Really Lies, Alvin Plantinga distinguished three ways in which scientific theories and theism might be related: apparent conflict, genuine conflict, and concord. [1] I take it as obvious that there does not exist even apparent conflict between contemporary cosmogonic theories and theism. Contemporary cosmology would therefore seem to be an area of obvious concord between science and theism.

But tonight I want to defend an even stronger claim, namely, that the evidence of contemporary cosmology actually renders God’s existence considerably more probable than it would have been without it:

Pr (Theism | Contemporary Cosmology & Background Information)

>> Pr (Theism | Background Information)

This is not to make some sort of naïve claim that contemporary cosmology proves the existence of God. There is no God-of-the-gaps reasoning here. Rather I’m saying that contemporary cosmology provides significant evidence in support of premises in philosophical arguments for conclusions having theological significance.

For example, the key premise in the ancient kalam cosmological argument that

2. The universe began to exist.

is a religiously neutral statement which can be found in virtually any contemporary textbook on astronomy and astrophysics. It is obviously susceptible to scientific confirmation or disconfirmation on the basis of the evidence. [2]

So, to repeat, one is not employing the evidence of contemporary cosmology to prove the proposition that God exists but to support theologically neutral premises in philosophical arguments for conclusions that have theistic significance.

In tonight's discussion I’ll focus on two such arguments: the kalam cosmological argument from the origin of the universe and the teleological argument from the fine-tuning of the universe.

The Kalam Cosmological Argument

Consider first the kalam cosmological argument:

1. If the universe began to exist, then there is a transcendent cause which brought the universe into existence.

2. The universe began to exist.

3. Therefore, there is a transcendent cause which brought the universe into existence.

By “the universe,” I mean that reality which is studied by contemporary cosmology, that is to say, all of contiguous physical reality, which currently takes the form of space-time and its contents.

I take it that (1) is obviously true. [3] Rather the truly controversial premiss is (2). Traditional supporters presented philosophical arguments in support of (2), [4] which, for me, constitute its primary warrant. But they’re not the subject of tonight’s debate. Rather what’s emerged during the 20th century is remarkable empirical confirmation of the second premiss from the evidence of astrophysical cosmogony. Two independent but closely interrelated lines of physical evidence support premiss (2): evidence from the expansion of the universe and evidence from the second law of thermodynamics.

In saying that the cosmogonic evidence confirms (2), I am not saying that we are certain that (2) is true. Too many people mistakenly equate knowledge with certainty. When they say that we do not know that the universe began to exist, what they really mean is that we are not certain that the universe began to exist. But, of course, certainty is not the relevant standard here. The question is whether (2) is more plausible in light of the evidence than its contradictory. As Professor Carroll reminds us,

Science isn't in the business of proving things. Rather, science judges the merits of competing models in terms of their simplicity, clarity, comprehensiveness, and fit to the data. Unsuccessful theories are never disproven, as we can always concoct elaborate schemes to save the phenomena; they just fade away as better theories gain acceptance. [5]

Science cannot force you to accept the beginning of the universe; you can always concoct elaborate schemes to explain away the evidence. But those schemes will not fare well in displaying the aforementioned scientific virtues.

Even many who have expressed scepticism about premiss (2) admit that it is more plausibly true than not. For example, in my recent dialogue with Lawrence Krauss, he volunteered, “I’d bet our universe had a beginning, but I am not certain of it. . . . based on the physics that I know, I’d say it is a more likely possibility.” [6] This is to admit precisely what cosmologists like Alexander Vilenkin have contended all along: that the evidence makes it more likely than not that the universe began to exist. [7]

Evidence from the Expansion of the Universe

Consider, first, the evidence from the expansion of the universe. The standard (Friedman-LeMaître Robertson-Walker) big bang cosmogonic model implies that the universe is not infinite in the past but had an absolute beginning a finite time ago. Although advances in astrophysical cosmology have forced various revisions in the standard model, nothing has called into question its fundamental prediction of the finitude of the past and the beginning of the universe. Indeed, as James Sinclair has shown, the history of 20th century cosmogony has seen a parade of failed theories trying to avert the absolute beginning predicted by the standard model. [8] Meanwhile, a series of remarkable singularity theorems has increasingly tightened the loop around empirically tenable cosmogonic models by showing that under more and more generalized conditions, a beginning is inevitable. In 2003 Arvind Borde, Alan Guth, and Alexander Vilenkin were able to show that any universe which is, on average, in a state of cosmic expansion throughout its history cannot be infinite in the past but must have a beginning. [9] In 2012 Vilenkin showed that cosmogonic models which do not fall under this condition, including Professor Carroll’s own model, fail on other grounds to avert the beginning of the universe. Vilenkin concluded, “None of these scenarios can actually be past-eternal.” [10] “All the evidence we have says that the universe had a beginning.” [11]

The Borde-Guth-Vilenkin theorem proves that classical space-time, under a single, very general condition, cannot be extended to past infinity but must reach a boundary at some time in the finite past. Now either there was something on the other side of that boundary or not. If not, then that boundary is the beginning of the universe. If there was something on the other side, then it will be a non-classical region described by the yet to be discovered theory of quantum gravity. In that case, Vilenkin says, it will be the beginning of the universe. [12]

Think about it. If there is such a non-classical region, then it is not past eternal in the classical sense. But neither can it exist literally timelessly, akin to the way in which philosophers consider abstract objects to be timeless or theologians take God to be timeless. For this region is in a state of constant flux, which, given the Indiscernibility of Identicals, is sufficient for time. [13] So even if time as defined in classical physics does not exist at such an era, some sort of time would. [14]

But if the quantum gravity era is temporal, it cannot be extended infinitely in time, for such a quantum state is not stable and so would either produce the universe from eternity past or not at all. As Anthony Aguirre and John Kehayias argue,

It is very difficult to devise a system – especially a quantum one – that does nothing ‘forever,’ then evolves. A truly stationary or periodic quantum state, which would last forever, would never evolve, whereas one with any instability will not endure for an indefinite time. [15]

Hence, the quantum gravity era would itself have to have had a beginning in order to explain why it transitioned just some 13 billion years ago into classical time and space. Hence, whether at the boundary or at the quantum gravity regime, the universe probably began to exist.

Evidence from Thermodynamics

Consider now the evidence from thermodynamics. According to the second law of thermodynamics entropy in a closed system almost never decreases. Given the naturalistic assumption that the universe is a closed system, the second law implies that, given enough time, the universe will come to a state of thermodynamic heat death, whether cold or hot. Given that the universe will expand forever, it may never reach a state of equilibrium, but it will grow increasingly cold, dark, dilute, and dead. But then the obvious question arises: why, if the universe has existed forever, is it not now in a cold, dark, dilute, and lifeless state? P. C. W. Davies gives the obvious answer: “The universe can’t have existed forever. We know there must have been an absolute beginning a finite time ago.” [16] The universe’s energy, says Davies, was simply “put in” at the creation as an initial condition. [17]

By contrast Professor Carroll’s solution to the problem confronts serious obstacles. He imagines that the overall condition of the universe is a state of thermal equilibrium (a sort of de Sitter space), but that random fluctuations spawn baby universes, which pinch off to become wholly independent space-times. We find ourselves in one such baby universe in a state of disequilibrium.

Let me raise two concerns about this model. First, not only are the production mechanisms of such baby universes admittedly conjectural, but such a scenario violates the so-called unitarity of quantum theory by allowing irretrievable information loss from the mother universe to the babies. Stephen Hawking, apologizing to science-fiction fans everywhere, came to admit, “There is no baby universe branching off, as I once thought. The information remains firmly in our universe.” [18]

Second, Professor Carroll’s solution provides no convincing answer to the Boltzmann Brain problem. Since the mother universe is a de Sitter space in which thermal fluctuations occur and since baby universes grow into de Sitter spaces themselves, there’s no explanation in the model why there exists a genuine low entropy universe around us rather than the mere appearance of such a world, an illusion of isolated brains which have fluctuated into existence out of the quantum vacuum. These and other problems make Professor Carroll’s model less plausible than the standard solution that the universe began to exist with an initial low entropy condition.

Skeptics might hope that quantum cosmology might serve to avert the implications of the second law of thermodynamics. But now a new singularity theorem formulated by Aron Wall seems to close the door on that possibility. Wall shows that, given the validity of the generalized second law of thermodynamics in quantum cosmology, the universe must have begun to exist, unless, as in Professor Carroll’s model, one postulates a reversal of the arrow of time at some point in the past, which, he rightly observes, involves a thermodynamic beginning in time which “would seem to raise the same sorts of philosophical questions that any other sort of beginning in time would.” [19] Wall reports that his results require only certain basic concepts, so that “it is reasonable to believe that the results will hold in a complete theory of quantum gravity.” [20]

Summary

Thus, we have good evidence both from the expansion of the universe and from the second law of thermodynamics that the universe is not past eternal but had a temporal beginning. So the second premise of the kalam cosmological argument receives significant confirmation from the evidence of contemporary cosmology. We have, then, a good argument for a transcendent cause of the universe.

The Teleological Argument

Turn now to the teleological argument from the fine-tuning of the universe. Scientists have been stunned by the discovery that the existence of intelligent, interactive life depends upon a complex and delicate balance of fundamental constants and quantities, like the gravitational constant and the amount of entropy in the early universe, which are fine-tuned to a degree that is literally incomprehensible.

Now there are three possibilities debated in the literature for explaining the presence of this remarkable fine-tuning: physical necessity, chance, or design. The question then is: Which of these three alternatives is the most plausible? On the basis of the evidence we may argue:

1. The fine-tuning of the universe is due to either physical necessity, chance, or design.

2. It is not due to physical necessity or chance.

3. Therefore, it is due to design.

Physical Necessity?

Consider the first alternative, physical necessity.

This alternative seems extraordinarily implausible because the constants and quantities are independent of the laws of nature. The laws of nature are consistent with a wide range of values for these constants and quantities. For example, the most promising candidate for a Theory of Everything (T.O.E.) to date, super-string theory or M-Theory, allows a “cosmic landscape” of around 10500 different universes governed by the present laws of nature, so that it does nothing to render the observed values of the constants and quantities physically necessary.

Chance?

So what about the second alternative, that the fine-tuning is due to chance? The problem with this alternative is that the odds against the universe’s being life-permitting are so incomprehensibly great that they cannot be reasonably faced. In order to rescue the alternative of chance, its proponents have therefore been forced to adopt the hypothesis that there exists a sort of World Ensemble or multiverse of randomly ordered universes of which our universe is but a part. Now comes the key move: since observers can exist only in finely tuned worlds, of course we observe our universe to be fine-tuned!

So this explanation of fine-tuning relies on (i) the existence of a specific type of World Ensemble and (ii) an observer self-selection effect. Now this explanation, wholly apart from objections to (i), faces a very formidable objection to (ii), namely, the Boltzmann Brain problem. In order to be observable the entire universe need not be fine-tuned for our existence. Indeed, it is vastly more probable that a random fluctuation of mass-energy would yield a universe dominated by Boltzmann Brain observers than one dominated by ordinary observers like ourselves. In other words, the observer self-selection effect is explanatorily vacuous. As Robin Collins has noted, what needs to be explained is not just intelligent life, but embodied, interactive, intelligent agents like ourselves. [21] Appeal to an observer self-selection effect accomplishes nothing because there’s no reason whatever to think that most observable worlds or the most probable observable worlds are worlds in which that kind of observer exists. Indeed, the opposite appears to be true: most observable worlds will be Boltzmann Brain worlds.

Since we presumably are not Boltzmann Brains, that fact strongly disconfirms a naturalistic World Ensemble or multiverse hypothesis.

Design?

It seems, then, that the fine-tuning is not plausibly due to physical necessity or chance. Therefore, we ought to prefer the hypothesis of design unless the design hypothesis can be shown to be just as implausible as its rivals. I’ll leave it up to Professor Carroll present any such objections.

Summary and Conclusion

In summary, it seems to me that the evidence of contemporary cosmology provides significant support for key premises in two philosophical arguments for conclusions having theological significance.

Thus, the existence of a Creator and Designer of the universe seems to be significantly more probable in light of contemporary cosmology than it would have been without it. [22]

Dr. Carroll - Opening Speech

Well thank you very much, it’s a great pleasure to be here. The Greer-Heard Forum has been very wonderful. I thank Dr. Craig for participating. For everyone here I appreciate your attendance, and I need to add a word of appreciation to this beautiful chapel that we’re holding the event in. I just hope that somewhere in the middle of my talking the roof does not fall on my head. But if it does that would be evidence and I would update my beliefs accordingly.

I also want to start with a confession that my goal here is not to win a debate. The discussion we are having tonight does not reflect a debate that is ongoing in the professional cosmology community. If you go to cosmology conferences there’s a lot of talk about the origin and nature of the universe; there is no talk about what role God might have played in bringing the universe about. It is not an idea that is taken seriously. My goal is to explain why we think that. You may or may not agree with me at the end but you should be able to understand why we cosmologists have that view. And it comes down to a conflict between two major fundamental pictures of the world—what philosophers would call ontologies: naturalism and theism. Naturalism says that all that exists is one world, the natural world, obeying laws of nature, which science can help us discover. Theism says that in addition to the natural world there is something else, at the very least, God. Perhaps there are other things as well. I want to argue that naturalism is far and away the winner when it comes to cosmological explanation. And it comes down to three points. First, naturalism works—it accounts for the data we see. Second, the evidence is against theism. Third, theism is not well defined. I’m going to be emphasizing this third point because if you ask a theist about the definition they will give you some very rigorous sounding definition of what they mean by God. The most perfect being, the ground for all existence, and so forth. There are thousands of such definitions, which is an issue, but the real problem is not with the definition, it’s when you connect the notion of God to the world we observe. That’s where apparently an infinite amount of flexibility comes in and I’m going to be inveighing against using that in cosmology.

So, I think I can make these points basically by following Dr. Craig’s organization starting with the kalam cosmological argument, and unlike what he said I should be doing I want to challenge the first of the premises: If the universe began to exist it has a transcendent cause. The problem with this premise is that it is false. There’s almost no explanation or justification given for this premise in Dr. Craig’s presentation. But there’s a bigger problem with it, which is that it is not even false. The real problem is that these are not the right vocabulary words to be using when we discuss fundamental physics and cosmology. This kind of Aristotelian analysis of causation was cutting edge stuff 2,500 years ago. Today we know better. Our metaphysics must follow our physics. That’s what the word metaphysics means. And in modern physics, you open a quantum field theory textbook or a general relativity textbook, you will not find the words “transcendent cause” anywhere. What you find are differential equations. This reflects the fact that the way physics is known to work these days is in terms of patterns, unbreakable rules, laws of nature. Given the world at one point in time we will tell you what happens next. There is no need for any extra metaphysical baggage, like transcendent causes, on top of that. It’s precisely the wrong way to think about how the fundamental reality works. The question you should be asking is, “What is the best model of the universe that science can come up with?” By a model I mean a formal mathematical system that purports to match on to what we observe. So if you want to know whether something is possible in cosmology or physics you ask, “Can I build a model?” Can I build a model where the universe had a beginning but did not have a cause? The answer is yes. It’s been done. Thirty years ago, very famously, Stephen Hawking and Jim Hartle presented the no-boundary quantum cosmology model. The point about this model is not that it’s the right model, I don’t think that we’re anywhere near the right model yet. The point is that it’s completely self-contained. It is an entire history of the universe that does not rely on anything outside. It just is like that. The demand for more than a complete and consistent model that fits the data is a relic of a pre-scientific view of the world. My claim is that if you had a perfect cosmological model that accounted for the data you would go home and declare yourself having been victorious.

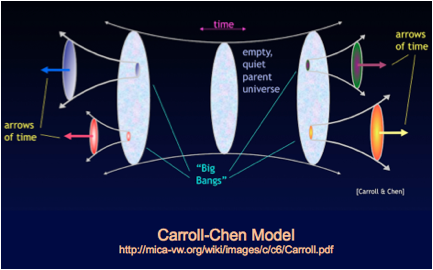

You might also ask, “Could the universe be eternal?” (since Dr. Craig talked about this) without having a beginning at all. Again, the answer is: yes, just build a model. This is my favorite model. It’s actually not even a model that I think is right; once again, it’s a model I helped create. But it’s about the search for models, not about saying any one model is the right idea. We hope that some day we get there but we don’t claim that we are there yet. So whether or not the universe can be eternal does not come down to a conversation about abstract principles. It comes down to a conversation about building models and seeing which one provides the best account for what we see the universe to be doing.

So I’d like to talk about the Borde-Guth-Vilenkin theorem since Dr. Craig emphasizes it. The rough translation is that in some universes, not all, the space-time description that we have as a classical space-time breaks down at some point in the past. Where Dr. Craig says that the Borde-Guth-Vilenkin theorem implies the universe had a beginning, that is false. That is not what it says. What it says is that our ability to describe the universe classically, that is to say, not including the effects of quantum mechanics, gives out. That may be because there’s a beginning or it may be because the universe is eternal, either because the assumptions of the theorem were violated or because quantum mechanics becomes important. If you need to invoke a theorem, because that’s what you like to do rather than building models, I would suggest the quantum eternity theorem. If you have a universe that obeys the conventional rules of quantum mechanics, has a non-zero energy, and the individual laws of physics are themselves not changing with time, that universe is necessarily eternal. The time parameter in Schrödinger’s equation, telling you how the universe evolves, goes from minus infinity to infinity. Now this might not be the definitive answer to the real world because you could always violate the assumptions of the theorem but because it takes quantum mechanics seriously it’s a much more likely starting point for analyzing the history of the universe. But again, I will keep reiterating that what matters are the models, not the abstract principles.

Dr. Craig brings up an argument about the Second Law of Thermodynamics and I’ve written a whole book, you can buy it on Amazon right now from your iPhones, about the second law and its relationship to cosmology. It is certainly a true issue that we don’t know why the early universe had a low entropy and entropy has ever been increasing. That’s a good challenge for cosmology. To imagine the cosmologist cannot answer that question without somehow invoking God is a classic god-of-the-gaps move. I know that Dr. Craig says that is not what he’s doing but then he does it. We don’t know why the early universe had a low entropy but that is not an argument that we can’t figure it out. There is more than one possibility. Maybe there is a principle, like Stephen Hawking would say, that puts the early universe in a low entropy state. Or maybe there is no high entropy state. In my model of an eternal universe the reason why our universe is always changing is because the universe always can change. There is no equilibrium for it to fall into. Dr. Craig brings up a quote – he brings up various things that I think really muddle the cosmological picture here. He says that my model is not working very well because it violates unitarity—the conservation of information—and that is straightforwardly false. In my model unitarity is the whole point. There’s a quantum mechanical wave function that describes the evolution of the universe from one piece into multiple pieces and that evolution is perfectly unitarity. He quotes Stephen Hawking backsliding his statement about baby universes but that was in the context of black holes. That had nothing to do with cosmology. That quote was taken completely out of context. Finally, he makes a big deal about Boltzmann Brains. I’m going to talk about that a little bit later. Most importantly, he talks about the fact that if the universe is eternal and you have a Second Law of Thermodynamics then there must have been a moment in the middle when the entropy was lowest, and he calls this a thermodynamic beginning and he quotes another paper. That’s fine except it’s an equivocation on the word beginning. A thermodynamic beginning is not a beginning—it happens in the middle. It’s a moment in the history of the universe from which entropy is higher in one direction of time and the other direction of time. There is no room in such a conception for God to have brought the universe into existence at any one moment.

If you really believe that the beginning of the universe is an important piece of evidence for God, an eternal universe with a low entropy state in the middle is not helping your case. What you should be doing is trying to build models, like I said. So the question is, “Are there realistic models of eternal cosmologies?” Well, I spent half an hour on the Internet and I was able to come up with about seventeen different plausible looking models of eternal cosmologies. I do not claim that any of these are the right answer. We’re nowhere near the right answer yet but you can come up with objections to every one of these models. You cannot say that they are not eternal. There’s a theorem, Borde-Guth-Vilenkin, that has assumptions so if you violate those assumptions you can violate the theorem. Meanwhile, theism, I would argue, is not a serious cosmological model. That’s because cosmology is a mature subject. We care about more things than just creating the universe. We care about specific details. At the cosmology conferences we’re discussing these questions that you see before you. I’m not going to list all of them but a real cosmological model wants to predict. What is the amount of density perturbation in the universe? And so forth. Theism does not even try to do this because ultimately theism is not well defined.

So let’s go to the second argument, the teleological argument from fine-tuning. I’m very happy to admit right off the bat – this is the best argument that the theists have when it comes to cosmology. That’s because it plays by the rules. You have phenomena, you have parameters of particle physics and cosmology, and then you have two different models: theism and naturalism. And you want to compare which model is the best fit for the data. I applaud that general approach. Given that, it is still a terrible argument. It is not at all convincing. I will give you five quick reasons why theism does not offer a solution to the purported fine-tuning problem.

First, I am by no means convinced that there is a fine-tuning problem and, again, Dr. Craig offered no evidence for it. It is certainly true that if you change the parameters of nature our local conditions that we observe around us would change by a lot. I grant that quickly. I do not grant therefore life could not exist. I will start granting that once someone tells me the conditions under which life can exist. What is the definition of life, for example? If it’s just information processing, thinking or something like that, there’s a huge panoply of possibilities. They sound very “science fiction-y” but then again you’re the one who is changing the parameters of the universe. The results are going to sound like they come from a science fiction novel. Sadly, we just don’t know whether life could exist if the conditions of our universe were very different because we only see the universe that we see.

Secondly, God doesn’t need to fine-tune anything. We talk about the parameters of physics and cosmology: the mass of the election, the strength of gravity. And we say if they weren’t the numbers that they were then life itself could not exist. That really underestimates God by a lot, which is surprising from theists, I think. In theism, life is not purely physical. It’s not purely a collection of atoms doing things like it is in naturalism. I would think that no matter what the atoms were doing God could still create life. God doesn’t care what the mass of the electron is. He can do what he wants. The only framework in which you can honestly say that the physical parameters of the universe must take on certain values in order for life to exist is naturalism.

The third point is that the fine-tunings you think are there might go away once you understand the universe better. They might only be apparent. There’s a famous example theists like to give, or even cosmologists who haven’t thought about it enough, that the expansion rate of the early universe is tuned to within 1 part in 1060. That’s the naïve estimate, back of the envelope, pencil and paper you would do. But in this case you can do better. You can go into the equations of general relativity and there is a correct rigorous derivation of the probability. If you ask the same question using the correct equations you find that the probability is 1. All set of measure zeroof early universe cosmologies have the right expansion rate to live for a long time and allow life to exist. I can’t say that all parameters fit into that paradigm but until we know the answer we can’t claim that they’re definitely finely-tuned.

Number four, there’s an obvious and easy naturalistic explanation in the form of the cosmological multiverse. People like to worry about the multiverse. It sounds extravagant. I claim the multiverse is amazingly simple. It is not a theory, it is a prediction of physical theories that are themselves quite elegant, small, and self-contained that create universes after universes. There’s no reason, no right that we have, to expect that the whole entire universe look like the conditions we have right now. But more importantly, if you take the multiverse as your starting point you can make predictions. We live in an ensemble and we should be able to predict the likelihoods that conditions around us take different forms. So in cosmology papers dealing with the multiverse you see graphs like this [slide image] that try to predict the density of dark matter given other conditions in the multiverse. You do not see graphs like this in the theological papers trying to give God credit for explaining the fine-tuning because theism is not well defined.

Now Dr. Craig makes a lot about the Boltzmann Brain problem. The problem that in the multiverse we could just be random fluctuations rather than growing in the aftermath of a hot big bang. This is a significant misunderstanding of how the multiverse works. The multiverse doesn’t say that everything that can possibly happen happens with equal probability. It says that there’s a definite history of the multiverse and you can make predictions. Different multiverse models will have different ratios of ordinary observers to random observers. That’s a good thing. That helps us distinguish between viable models of the multiverse and non-viable models, and there are plenty of viable models where the Boltzmann Brain, or random fluctuations, do not dominate. Furthermore, just as a little preview of coming attractions, I’m trying to write a paper (when I’m not debating about God and cosmology; I’m a physicist). I’m currently working on a paper that says, actually, Boltzmann Brains (random fluctuations) occur much, much less frequently than we previously believed. It comes down to a better understanding of quantum fluctuations. There’s a caricature of theism that says theism is an excuse to stop thinking. You say, “Oh, there’s a problem, I don’t need to solve it because God will solve it for me.” That’s clearly false because many theists think very carefully and very rigorously about many problems. But sometimes there’s an element of truth to it. This is an example. You’re faced with the Boltzmann Brain problem and you go, “I get out of that by saying that God created a single universe.” That might have stopped you from thinking about the physics in a deeper way and discovering interesting facts like this.

Fifth, and most importantly, theism fails as an explanation. Even if you think the universe is finely-tuned and you don’t think that naturalism can solve it, theism certainly does not solve it. If you thought it did, if you played the game honestly, what you would say is, “Here is the universe that I expect to exist under theism. I will compare it to the data and see if it fits.” What kind of universe would we expect? I’ve claimed that over and over again the universe we would expect matches the predictions of naturalism not theism. So the amount of tuning, if you thought that the physical parameters of our universe were tuned in order to allow life to exist, you would expect enough tuning but not too much. Under naturalism, a physical mechanism could far over-tune by an incredibly large amount that has nothing to do with the existence of life and that is exactly what we observe. For example, the entropy of the early universe is much, much, much, much lower than it needs to be to allow for life. You would expect under theism that the particles and parameters of particle physics would be enough to allow life to exist and have some structure that was designed for some reason whereas under naturalism you’d expect them to be kind of random and a mess. Guess what? They are kind of random and a mess. You would expect, under theism, for life to play a special role in the universe. Under naturalism, you would expect life to be very insignificant. I hope I don’t need to tell you that life is very insignificant as far as the universe is concerned.

Here is a photograph [slide image] from the Hubble Space Telescope of a few hundred out of the hundreds of billions of galaxies in our observable universe. The theistic explanation for cosmological fine-tuning asks you to look at this picture and say, “I know why it is like that. It’s because I was going to be here or we were going to be here.” But there is nothing in our experience of the universe that justifies the kind of flattering story we like to tell about ourselves. In fact, I would argue that the failure of theism to explain the fine-tuning of the universe is paradigmatic. It helps understand the other ways in which theism fails to be a better theory than naturalism. What you should be doing over and over again is comparing the predictions or expectations under theism to under naturalism and you find that over and over again naturalism wins. I’m going to zoom through these. It’s not the individual arguments that are important, it’s the cumulative effect.

If theism were really true there’s no reason for God to be hard to find. He should be perfectly obvious whereas in naturalism you might expect people to believe in God but the evidence to be thin on the ground. Under theism you’d expect that religious beliefs should be universal. There’s no reason for God to give special messages to this or that primitive tribe thousands of years ago. Why not give it to anyone? Whereas under naturalism you’d expect different religious beliefs inconsistent with each other to grow up under different local conditions. Under theism you’d expect religious doctrines to last a long time in a stable way. Under naturalism you’d expect them to adapt to social conditions. Under theism you’d expect the moral teachings of religion to be transcendent, progressive, sexism is wrong, slavery is wrong. Under naturalism you’d expect they reflect, once again, local mores, sometimes good rules, sometimes not so good. You’d expect the sacred texts, under theism, to give us interesting information. Tell us about the germ theory of disease. Tell us to wash our hands before we have dinner. Under naturalism you’d expect the sacred texts to be a mishmash—some really good parts, some poetic parts, and some boring parts and mythological parts. Under theism you’d expect biological forms to be designed, under naturalism they would derive from the twists and turns of evolutionary history. Under theism, minds should be independent of bodies. Under naturalism, your personality should change if you’re injured, tired, or you haven’t had your cup of coffee yet. Under theism, you’d expect that maybe you can explain the problem of evil – God wants us to have free will. But there shouldn’t be random suffering in the universe. Life should be essentially just. At the end of the day with theism you basically expect the universe to be perfect. Under naturalism, it should be kind of a mess—this is very strong empirical evidence.

Now, I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking, “But I can explain all of that.” I know you can explain all of that—so can I. It’s not hard to come up with ex post facto justifications for why God would have done it that way. Why is it not hard? Because theism is not well defined. That’s what computer scientists call a bug, not a feature.

Immanuel Kant famously said, “There will never be an Isaac Newton for a blade of grass.” In other words, sure you can find some physical explanation for the motion of the planets but never for something as exquisitely organized and complex as a biological organism. Except, of course, that Charles Darwin then went and did exactly that. We can paraphrase Dr. Craig’s message as saying there will never be an Isaac Newton for the cosmos but everything we know about the history of science and the current state of physics says we should be much more optimistic than that. Thank you.

Dr. Craig - Rebuttal Speech

Thank you, Dr. Carroll, for that vigorous interaction!

Introductory Remarks

In my opening speech, I argued that God’s existence is significantly more probable given the evidence of contemporary cosmology than it would have been without it. This is due to the support which cosmology lends to key premises in the cosmological and teleological arguments.

Before we review those arguments, let me just say a word about Professor Carroll’s concluding remarks, which, I believe, are extraneous to tonight’s discussion.

He is very concerned to show that God’s existence is improbable relative to certain non-cosmological data. For example, the problem of evil, our insignificant size, and so forth. The very fact that these are non-cosmological data shows that they are not relevant in tonight’s debate. I have addressed things like the problem of evil extensively, for example, in Philosophical Foundations for a Christian Worldview. [23] So the debate tonight is not over the probability of theism versus naturalism. That would require us to assess all sorts of non-cosmological data. Rather, the question is: is God’s existence more probable given the data of contemporary cosmology than it would have been without it? And I think it certainly is.

Let’s look at those two arguments that I defended.

The Kalam Cosmological Argument

Consider, first, the evidence for the beginning of the universe from the expansion of the universe and thermodynamics.

The Causal Premise

To my surprise, Dr. Carroll challenges the first premise of this argument by saying it is based on outmoded Aristotelian concepts of causality. I protest – not at all! There is no analysis given of what it means to be a cause in this first premise. You can adopt your favorite theory of causation or take causation to be a conceptual primitive. All it requires is that the universe did not pop into being uncaused out of absolutely nothing. If that is the price of non-theism, then I think the non-theist is welcome to it. Dr. Carroll says on the Hartle-Hawking model the universe is uncaused. Not at all! The universe comes into being on such a model, and there is nothing in the theory that would explain why that universe exists rather than not. The model may be self-contained; but that is perfectly consistent with my argument. I am not arguing for some kind of interventionist deity, but rather, why does the universe exist? Why did it come into being at all?

Evidence from the Expansion of the Universe

With respect to the second premise, Dr. Carroll says there are all kinds of beginningless models of the universe. Well, it certainly is true that such models exist; but the problem is that none of them is successful.

|

Beginningless Models |

||

|

Model average expansion history |

Condition requiring a beginning |

|

|

1 |

Expanding models |

Singularity theorems |

|

2 |

Asymptotically static models |

Metastability |

|

3 |

Cyclic models |

Second Law of Thermodynamics |

|

4 |

Contracting models |

Acausal fine-tuning |

As Jim Sinclair has shown in our article in the Blackwell Companion, all of the models that Dr. Carroll has mentioned have been shown to be either untenable or not to avert the beginning of the universe. [24] Alex Vilenkin says flatly, “there are no models at this time that give a satisfactory model for a universe without a beginning.” [25]

Consider in particular Dr. Carroll’s own model.

This model presupposes a reductionistic view of time according to which the direction of time is defined in terms of entropy increase. Now, in the model notice there are two arrows of time for the mother universe pointing in opposite directions. So on this view of time, we don’t really have an eternally existing mother universe here at all. Rather, you have two universes which share a common origin in the central surface. So what the model actually implies, rather than avoids, is a beginning of time and of the universe. Time has a beginning on this model, and therefore it involves all of the problems that are pertinent to the universe’s coming into being.

Be that as it may, I think it is safe to say that there is no credible classical model of a beginningless universe today.

Dr. Carroll does hold out hope that quantum cosmology might serve to restore the past eternality of the universe; but I would say that not only is there no evidence for such a hope, but I would agree with Vilenkin that if there is a quantum gravity regime prior to the Planck Time, then that just is the beginning of the universe. Dr. Carroll says you can have quantum descriptions of the universe that are eternal, and that is certainly true, but the question is: why would the universe transition to classical spacetime just 13 billion years ago? It could not have existed from infinity past in an unstable quantum state and then just 13 billion years ago transition to classical spacetime. It would have done it from eternity past, if at all.

So I think we’ve got good evidence from the expansion of the universe that the universe probably began to exist.

Evidence from Thermodynamics

What about the evidence from thermodynamics? First is the problem of information loss to baby universes on his theory. You will recall that is why Stephen Hawking rejected the baby universe hypothesis. Dr. Carroll responds, “My mechanisms for generating the baby universes don’t use Hawking’s mechanisms.” All right; but are they any more successful? I don’t think so. According to Chris Weaver in his article on the Carroll-Chen model,

The FGG [Farhi-Guth-Guven] nucleation [that Dr. Carroll uses] out of a de Sitter space-time is merely speculative and . . . Carroll’s discussion of it should be thought of as exploratory. . . . it is therefore safe to conclude that a central piece of the model is missing, and so the CC-M [Carroll-Chen model] is incomplete in that it does not have a clear recommended dynamical path from the background [space-time] to the birth of [universes] like ours. [26]

In fact, Weaver goes on to point out that for a universe described by the Borde-Guth-Vilenkin theorem (like ours), the Farhi-Guth-Guven mechanisms cannot produce such a universe. Therefore, these mechanisms fail.

I also, secondly, pointed out that there is a Boltzmann Brain problem with respect to Dr. Carroll’s model. It seems to me that he just didn’t respond to the point that I was making, namely, that since every baby universe grows into a de Sitter space, there will be vastly, vastly more of these Boltzmann Brains in the long run than there will be ordinary observers. So what Dr. Carroll would need to do is to justify some non-standard measure of probability that would make ordinary observers more probable than Boltzmann Brains. But he admits that he cannot do it.

We also then saw that quantum gravity will not avert this conclusion because of the Wall theorem, which should be valid for the quantum gravity era and requires a beginning of the universe.

Summary

So it seems to me we’ve got good evidence from the expansion of the universe and from thermodynamics that the universe is probably not past eternal but began to exist.

The Teleological Argument

What about that second argument based upon the fine-tuning of the universe?

Reality of Fine-Tuning

Here Dr. Carroll expresses scepticism that the fine-tuning is real. But a good many, if not most, of his colleagues would simply disagree with him here. Luke Barnes provides a list of just some of the scientists who have published works in defense of the reality of fine-tuning:

I can think of one more name that we should add to the list – namely, Sean Carroll! Listen to what he has to say about the low entropy condition of the early universe, which Robin Collins calls “potentially the most outstanding case of fine-tuning.” [27] Carroll writes, “If the universe we see is really all there is with the Big Bang as a low-entropy beginning, we seem to be stuck with an uncomfortable fine-tuning problem.” [28] So he tries to explain away this fine-tuning via the world ensemble, or multiverse, hypothesis.

Chance?

But then, as I argued in my opening speech, he confronts the Boltzmann Brain problem once again. Even if Dr. Carroll could show that ordinary observers predominate in life-permitting worlds, what about all of those worlds that are not life-permitting because the other constants and quantities are not finely-tuned? In such worlds – which vastly outnumber finely-tuned worlds – there will be no ordinary observers, and yet there will be untold numbers of Boltzmann Brains produced by thermal fluctuations. So the entire multiverse will be dominated by universes having vastly more Boltzmann Brains than ordinary observers like us. [29] Therefore, the data on the multiverse hypothesis is incomprehensibly improbable. The evidence is strongly disconfirmatory of the World Ensemble hypothesis.

Design?

Dr. Carroll says that theism does no better in accounting for the low entropy condition of the universe. For why, he asks, did God make the entropy of the universe so unnecessarily low in order to create us? Well, I have two responses to this. First, it is no part of the fine-tuning argument to assert that the purpose for which the universe was created is us! There may well be intelligent life created by God scattered throughout the universe. But, secondly, as Robin Collins has pointed out, even if a general low entropy condition is not necessary for our existence, it is necessary for the discoverability of the universe. God hasn’t given us an instruction manual about how the world works. But what he has done is make a world which is susceptible to rational exploration and discovery. And if God wanted to make a universe discoverable by embodied, conscious agents, he might well make it in such a low entropy condition. (You will hear more about that tomorrow when Robin gives his paper.)

So it seems to me that Dr. Carroll faces uniquely a Boltzmann Brain problem for a number of reasons – a problem that does not afflict theism.

Summary and Conclusion

So, in summary, this is not a debate between naturalism and theism. Otherwise, I would be offering ontological arguments, moral arguments, other sorts of arguments. For that debate, you need to listen to my debate with Dr. Rosenberg last year at Purdue University. What this debate is about is: to what degree do the data of contemporary cosmology render God’s existence more probable than it would have been if we didn’t have that data? To my mind, it is almost undeniable that God’s existence is much more probable given the evidence that we have for the beginning of the universe and the fine-tuning of the universe. Therefore, contemporary cosmology is strongly confirmatory of theism.

Dr. Carroll - Rebuttal Speech

Great. Well, thanks again. I think that we can just go right back to my three major points, and I think that, halfway through our forum, I believe these three major points more strongly than ever. Now, I know that Dr. Craig would disagree but I’ll try to establish that his disagreements with number one are based on misunderstandings of the science. His disagreements with number two, the evidences against theism, is largely based on using number three—the fact that theism is not well defined.

So let’s go to the kalam cosmological argument. There’s a deep philosophical difference between us. I claim that a consistent, complete model that fits the data accounts for what we see in the world is a success. There’s no right that we have to demand more than that, and I believe that Dr. Craig’s response was, “Yes there is.” I don’t think this counts as a very good response. It’s a very difficult thing because the universe is different than our everyday experience. That doesn’t sound like a surprising statement but we really need to take it to heart. To look at a modern cosmological model and say, “Yes, but what was the cause?” is like looking at someone taking pictures with an iPhone and saying, “But where does the film go?” It’s not that the answer is difficult or inscrutable; it’s completely the wrong question to be asking. In fact it’s a little technical, most of my second talk here, but I think it’s worth getting it right. Why should we expect that there are causes or explanations or a reason why in the universe in which we live? It’s because the physical world inside of which we’re embedded has two important features. There are unbreakable patterns, laws of physics—things don’t just happen, they obey the laws—and there is an arrow of time stretching from the past to the future. The entropy was lower in the past and increases towards the future. Therefore, when you find some event or state of affairs B today, we can very often trace it back in time to one or a couple of possible predecessor events that we therefore call the cause of that, which leads to B according to the laws of physics. But crucially, both of these features of the universe that allow us to speak the language of causes and effects are completely absent when we talk about the universe as a whole. We don’t think that our universe is part of a bigger ensemble that obeys laws. Even if it’s part of the multiverse, the multiverse is not part of a bigger ensemble that obeys laws. Therefore, nothing gives us the right to demand some kind of external cause.

The idea that our intuitions about cause and effect that we get from the everyday experience of the world in this room should somehow be extended without modification to the fundamental nature of reality is fairly absurd. On a more specific level we talked about my model. Again, I’m not trying to defend my model; I’m the first one to say that it has problems. None of the problems that it has are the ones that Dr. Craig raised. He says that it’s not really eternal, which it is hard to express the extent to which I think this is grasping at straws. The axis for time goes from the top to the bottom and it goes forever. The only sense in which this universe is not eternal is that there is a moment in the middle where the entropy is lowest. I made the point in my opening speech that that has nothing to do with the kind of beginning you would need to give God room to work and as far I can recall Dr. Craig didn’t address that argument.

He does say that it is speculative, the idea of baby universes coming into existence. I’m the first to agree. It’s completely speculative. He quotes a paper that says the mechanism by which baby universe are created is speculative, it might not be right. Again, it’s completely true. He claims to use it to say that unitarity is violated even though the quote he read didn’t even mention unitarity and wasn’t about unitarity. That is not a sensible objection.

I will repeat – the quantum eternity theorem, a sensible analysis of the history of the universe, might be with the rules of quantum mechanics. He claims that someone else said there might be a singularity in quantum gravity but he gives us no understanding, he simply repeats his previous analysis. So, I want to draw attention not to my model but to the model of Anthony Aguirre and Steven Gratton because this is perfectly well defined. This is a bouncing cosmology that is infinite in time, it goes from minus infinity to infinity, it has classical description everywhere. There is no possible sense in which this universe comes into existence at some moment in time. I would really like Dr. Craig to explain to us why this universe is not okay.

Now there’s a theorem by Alan Guth, Arvind Borde, and Alex Vilenkin that says the universe had a beginning. I’ve explained to you why that’s not true but in case you do not trust me I happen to have Alan Guth right here. One of the authors of the Borde-Guth-Vilenkin Theorem, Alan what do you say? He says, “I don’t know whether the universe had a beginning. I suspect the universe didn’t have a beginning. It’s very likely eternal but nobody knows.” Now how in the world can the author of the Borde-Guth-Vilenkin theorem say the universe is probably eternal? For the reasons I’ve already told you. The theorem is only about classical descriptions of the universe not about the universe itself.

So, going to the teleological argument. It is true – Dr. Craig brings up the point that people disagree with me, it is true. I attempted to give an argument and not merely an opinion poll. If we’re allowed to take opinion polls I will poll my fellow cosmologists on whether God had anything to do with creating the universe and I will win by a landslide. I suspect that Dr. Craig thinks the majority of the opinions of cosmologists is important for some issues but not for others. The entropy of the early universe is exactly backwards when it comes to being an argument for fine-tuning according to theology. Dr. Craig quotes me in a “gotcha-moment” saying, “Look, the early universe was finely-tuned with a low entropy.” That is absolutely true. The point that I raised was not that there is not fine-tuning, it’s that there’s no evidence the fine-tuning is for life to exist. Indeed, the maximum possible entropy of the part of the universe we observe is this huge number, 10122. The entropy that you would need is a little bit lower than that if you wanted life to exist. But it’s almost the same. It’s 0.999 etc. times the maximum entropy, whereas the actual entropy of the early universe is enormously smaller than that. There’s absolutely no reason why the universe would look like this if the fine-tunings were put there in order for life to exist. I’m not saying there’s not fine-tunings; I’m saying they’re not there for life.

Turning to the multiverse, again it is a completely speculative thing, but it is a completely natural thing and I don’t really see any argument against that. The multiverse, the idea that outside the universe we see there could be very different regions with very different physical parameters, is no more radical then the idea that there are different planets with different atmospheres. To a frog on a lily pad that lily pad is its universe. To us in the universe we see a hundred billion galaxies is enough but it’s very, very easy to come up with physical models that have much more out there. The main argument Dr. Craig has against this is the Boltzmann Brain argument. Again, I gave you why that’s not a good argument and it seems to have been ignored in Dr. Craig’s last speech; namely that the multiverse does not predict that everything happens. It predicts certain things happen with certain frequencies. So what you do as a working cosmologist is check that your universe is not dominated by Boltzmann Brains. Are there multiverse models that pass that test? Yes, there are. It is easily avoided. Then he brings up this weird argument, he says, “There could be the regions where ordinary observers could not exist because the parameters are not right but Boltzmann Brains could exist.” But the whole point is that Boltzmann Brains are forms of life. Boltzmann Brains can only exist where life is possible. So what one does in cosmology is look at the multiverse regions where life is possible and counts the number of Boltzmann Brains versus the number of ordinary observers—there are models that pass the test.

Now, I think that this is, again, a philosophical point here because when I talked about the list of ways in which our expectations for theism come out completely wrong when you compare them to the world, Dr. Craig said, “Well, that’s not the point, we’re not arguing about morality” and things like that. But again that misses the point of my argument. I was not actually putting forward these as strong predictions of theism. I was making the point that there are no strong predictions of theism. It’s not that there should be no evil in the world if God exists, it’s that you can always wriggle out of the prediction that there should be no evil in the world if God exists. That’s why it’s not a good theory of the world generally, that’s why it’s not a good cosmological model, particularly. Now, Dr. Craig said that we shouldn’t expect to know things about the world simply because we say that God finely-tuned it. “Just because under theism,” he says, “God made the parameters of the universe such to allow life to exist doesn’t mean we can have any other expectation for predicting what those parameters are.” This reflects something that he said on his website earlier. In a similar context he said, “Suppose God is more like the cosmic artist who wants to splash his canvas with the extravagance of design and who enjoys creating this fabulous cosmos designed with fantastic detail for observers.” So, what this attitude is saying is that – well, my point is that – this is not some sort of sophisticated apologetic strategy. This is an admission of defeat. This is saying we should never expect theism to explain why the universe is one way rather than some other way. You know God—God is an artist. You know artists; they’re kind of quirky and unpredictable. We can’t expect to know what they’re going to do ahead of time. Anything you might possibly observe about the universe, according to this view, I can explain as saying, “That is what God would have done.”

In naturalism, on the other hand, you need to play by the rules. When we say in cosmology or physics that a certain parameter is finely-tuned, it’s not just the parameter looks funny to us, it’s that we have a prior set of expectations for what values the parameters should take on and the parameter doesn’t fit those expectations. So we look for physical models that explain it, and that drive to understand things better helps us understand physics better, helps us understand the real world better. So, unlike God who is an artist and can’t be predicted, nature is not an artist. Nature plays by the rules. Nature makes predictions. Nature provides explanations. Thank you.

Dr. Craig - Closing Speech

Perhaps you feel like you have been drinking from a fire hose this evening! But let me in my final speech try to draw together some threads of the debate and see if we can draw some conclusions.

Introductory Remarks

I hope that it has been obvious tonight that I am not offering God as a theory to compete with scientific theories about the universe. Rather, I am saying that those self-contained, secular theories provide evidence for theologically neutral premises in philosophical arguments leading to a conclusion that has theistic significance—premises like “The universe began to exist” or “The fine-tuning is not due to physical necessity or to chance.” If those premises are supported, then it follows deductively that there is a Creator and Designer of the universe. Dr. Carroll’s complaints about theism’s not making predictions would be important only if I were offering some sort of theistic theory of the world. But I am not doing so. I am simply appealing to the cosmological evidence in support of these theologically neutral premises that go to deductively imply the existence of a Creator and Designer.

Let’s look again at those arguments that I defended.

The Kalam Cosmological Argument

The Causal Premise

First, the kalam cosmological argument. Dr. Carroll challenges the first premise, that if the universe came into existence, there is a transcendent cause that brought the universe into being. Honestly, I am quite astonished that he would think that the universe can literally pop into being out of nothing. Let me just give three arguments for why there must be a cause.

First of all, it seems to me a metaphysical first principle that being doesn’t come from non-being. Things don’t just pop into existence from literally nothing. Nothingness has no properties, no potentialities. It is not anything. So it seems to me inconceivable metaphysically to think the universe can come into being from nothing.

Secondly, if the universe could come into being from nothing, then why is it that only universes can pop into being out of nothing? Why not bicycles and Beethoven and root beer? What makes nothingness so discriminatory? If universes could pop into being out of nothing, then anything and everything should pop into being out of nothing. Since it doesn’t, that suggests that things that come into being have causes.

Finally, all the empirical evidence we have supports the truth of the causal principle. When Dr. Carroll says, “The universe is different than our experience,” this is really committing what Alexander Pruss calls the taxi-cab fallacy, that is to say, you go with the causal principle until you reach your desired goal and then you think you can just dismiss it like a hack because you don’t want there to be a cause of your entity – the universe. But if the universe came into existence, if the universe is not eternal, then surely it would need to have a cause. In fact, to deny this is unscientific because the whole project of contemporary cosmogony is to try to find what is the cause of the universe! So on his principle, it would be a science-stopper and would destroy his very field of expertise.

Evidence from the Expansion of the Universe

With respect to the second premise that the universe did begin to exist, he denies that he actually has an origin of time going in two opposite directions.

But this is a different diagram of his model. [30] Notice that on this diagram, you have a non-reductionistic arrow of time that goes from past to future. This is not an arrow of time that is determined by entropy increase, as he had in the other diagram. This is a non-reductionistic view of time, that Professor Maudlin and I accept, where the direction of entropy increase doesn’t define the direction of time. On this model, the universe contracts down from eternity past from infinity to a relatively low entropy point and then begins to expand again. That kind of model is physically impossible. It contradicts the second law of thermodynamics. That is why you have got to have the arrows pointing in both directions, if you want to hope for this model to be realistic. But if you have a double-headed arrow of time in both directions, then you have a beginning of time and of the universe. So I want to co-opt Dr. Carroll’s model for myself! On his model of the universe, the universe began to exist, along with time.

I also pointed out that on the Borde-Guth-Vilenkin theorem, there are no classical models that succeed in showing the universe to be beginningless. He rightly points out this is just classical space-time. But then I never heard a response to my claim that if there is a quantum gravity era prior to the Planck time, then it would have to be itself finite because otherwise it becomes inexplicable why classical spacetime only came into being 13 billion years ago rather than from eternity past.

So I think we have got good evidence for the beginning of the universe from the expansion of the universe.

Evidence from Thermodynamics

As for thermodynamics, here I argued that in order to explain why we are in a low entropy state, the standard answer is that the universe began relatively recently with its low entropy condition at the beginning. By contrast, his model, I charged, violates the unitarity of quantum physics. He says, “No, because I am not using the same mechanisms as Hawking.” But then I pointed out that the mechanisms that he appeals to are both conjectural and actually incompatible with a universe described by the Borde-Guth-Vilenkin theorem, as Christopher Weaver points out in his critique of the model.

Secondly, the Boltzmann Brain problem. I don’t think that Dr. Carroll has really come to grips with this, quite honestly. There are at least two reasons why Boltzmann Brains would dominate. First, because on his multiverse model, in the long run every baby universe becomes a de Sitter space and will become dominated with Boltzmann Brains. Secondly, in all of the other worlds that are not fine-tuned, there just aren’t any ordinary observers; but there will be thermal fluctuations that will produce Boltzmann Brains. So he is the one who has to justify some non-standard measure of probability in order to explain why ordinary observers like us should exist rather than Boltzmann Brains.

Then I appealed to the Wall theorem to show that even on a quantum gravity theory you are not going to avoid the beginning of the universe. Dr. Carroll may have responded to this, but if he did, it went by so quick I didn’t hear it. So it seems to me we’ve still got the Wall theorem showing that even with a quantum gravity era there has to be a beginning.

The Teleological Argument

Design?

As to the teleological argument from fine-tuning, he seems to have rested his entire case here on the fact that entropy would be way, way unnecessarily too small on theism. But I gave two responses to that. First, there may be life throughout the universe, not just us. Secondly, as Robin has pointed out, the low entropy condition is suitable for the discoverability of the universe. By contrast, on his view, it is incomprehensibly improbable that we should exist, given the equilibrium or the heat death state at which the universe would more probably exist.

Summary and Conclusion

So, in sum, in seems to me that on balance that we have got good evidence that the universe began to exist and that, therefore, there must be a Creator that brought it into being. Moreover, this is a personal Designer of the universe in view of the fine-tuning of the universe for intelligent, interactive agents like ourselves.

Dr. Carroll - Closing Speech

All right, congratulations to everyone for having made it this far. I will confess a bit of frustration in this final talk because I think almost everything that Dr. Craig had said in his last talk he had already said, and I tried to give my best response to it. They weren’t always matched. So, I’m going to take advantage of that to do something bizarre and unpredictable, which I’ll get to in a second.

First, I want to notice some of the things he did say. He said he was astonished that I refused to accept the fact that things need causes to happen. To which I could only quote David Lewis, “I do not know how to refute an incredulous stare.” I tried to give the reason why the causation analysis that we use for objects within the universe does not apply to the universe but that more or less whizzed on by. Dr. Craig gets a lot of mileage out of the presumed nuttiness of things just popping into existence. “Why don’t bicycles just pop into existence?” Again, I tried to explain what makes the universe different but more importantly the phrase “popping into existence” is not the right one to use when you’re talking about the universe. It sounds as if it’s something that happens in time but that’s not the right way to do it because there’s no before the beginning, if there’s a beginning. The correct thing to say is there was a first moment of time. When you say it that way it doesn’t’ sound so implausible. The question is, is there a model in which that’s true? Do the equations of the model hang together? Does the model fit the data? And we have plausibly positive answers to all of those.

He spends a lot of time on my own model, more time than I would have spent on it. He is upset that I did not include an arrow at the bottom in my axis when I drew the graph previously. I don’t care about that to be very honest. The double arrows here are just to express the fact that there’s no intrinsic arrow of time. The arrow of time that we experience is because of the behavior of matter in the universe—the entropy increasing. And he says that’s in violation of the Second Law of Thermodynamics. Yes, it is an explanation of the Second Law of Thermodynamics. This is the reason why we in our little part of the universe observe the second law. He mentions once again Boltzmann Brains and he says that there should be more Boltzmann Brains than ordinary observers. I again explain why that’s not true because it’s a model dependent statement. In this particular model it turns out to be easier to make a universe than to make a brain. That’s a selling point of the model.

So, with that under our belts, I want to actually just completely go off the topic and talk about issues beyond naturalism and theism. We’re having a discussion here about God and cosmology but let’s pull back the curtain a little bit. There are very few people in the modern world who become religious, to come to believe in God, because it provides the best cosmology or because it provides the best physics or biology, or psychology, or anything like that. And that includes Dr. Craig. There’s a famous quote by him that says, “The real reason, the primary reason, for believing in Christianity isn’t cosmological arguments.” I’m not mentioning this as a criticism; it is simply an observation of fact. There are other reasons to be a theist other than cosmology, and I think that is true. I think that makes sense. Most people who become religious do so for other reasons—because it gives them a sense of community, a sense of connection with the transcendent, it provides meaning or fellowship in their lives. The problem is that the basis of religion in the modern Western world is theism, belief in the existence of God. I’ve tried to make the case that science undermines theism pretty devastatingly. Five hundred years ago it would have made perfect sense to be a theist. I would have been a theist five hundred years ago. By two hundred years ago science had progressed to the point where it was no longer the best theory. By a hundred years ago after Darwin it was a rout. And by these days with modern cosmology there’s no longer any reason to take that as your fundamental worldview.

So what do you do if you identify as a member of a religious tradition in this situation. I think there are three options. One is to deny the science, to think that the world is six thousand years old. Happily, nobody up here on this stage today takes that attitude. That was a previous debate from a couple weeks ago. But there is a second attitude which is to accept the science but deny the implications—to say that none of the progress of modern science has in any way altered the fundamental view of reality that we put together two thousand years ago. I think that there’s two reasons why that’s not a good idea. Number one, I think it’s wrong, as I tried to explain throughout the debate, but number two, I think it’s a strategic mistake. I think that if one believes in theism that must be central to one’s view of the world for many, many other reasons, and because theism has been undermined by science it takes theists and it marginalizes them as part of the wider intellectual conversation. Humanity is at a crossroads. It’s at a very important time in the history of the world. We need to have deep discussions about who we are and where we’re going, and people who cling to the belief in God after science has undermined it are increasingly not going to be part of that discussion.

We talked about cosmologists and physicists, here’s what philosophers believe. There’s a recent survey that asked philosophers thirty big questions. And you know philosophers don’t agree on anything, but here are the three questions they had the greatest amount of consensus on: external reality exists, science tells us something about that external reality, and God does not exist. Now, again, get three philosophers in a room and they don’t even agree that there are three philosophers in the room. So, the fact that there’s only 73% is a still very impressive, and this includes professional philosophers of religion.

So I claim that there is a third option. Here’s the point where I start giving people advice who did not ask me for any advice. So, I ask your indulgence here. The third option, as I see it, for the person who is religious is to say, “Look, we admit we were wrong. We were wrong hundreds of years ago when we based our belief system on the idea that God was in charge of it all. Of course we were wrong, it was two thousand years ago! We didn’t have microscopes or telescopes. What right do we have to think that we would have gotten the fundamental nature of reality right but,” this person could hypothetically say, “religion is much more than theism. It’s not just the belief in God. There is the fellowship we feel for our fellow human beings.” For centuries, religious traditions were the place where human beings did their most careful, sustained, and rigorous contemplation about what it means to be human, about what it means to experience joy or suffering, to feel camaraderie with your fellow man, to be charitable, and so forth—to have meaning and purpose in your lives. So, maybe this person could say there is something to be learned even for naturalists from the outcome of all that contemplation. Maybe there is wisdom in Scriptures and the Sermon on the Mount, in the art and the music and the lives of the saints, or for that matter, the Bhagavata Gita or the Daodejing. I don’t know whether there is wisdom there, I’m asking for guidance. At the end of the day we’re all human beings trying to figure out our way in this confusing world.