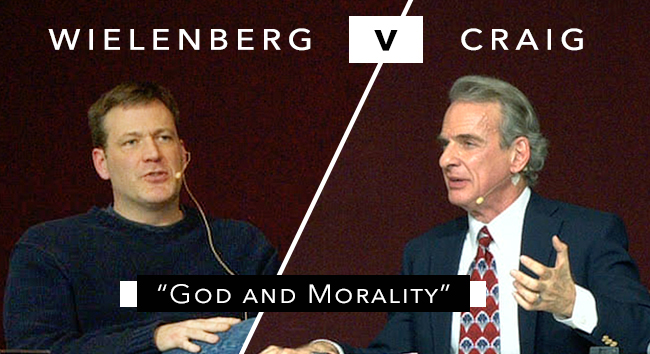

Moral Debate With Erik Wielenberg, Part Two

April 30, 2018 Time: 16:46

Summary

Dr. Craig continues commentary on this debate with Dr. Wielenberg

KEVIN HARRIS: Let's pick it up where we left off last time discussing your debate with Erik Wielenberg. What were your responses to godless normative realism?

DR. CRAIG: I presented two main objections to godless normative realism. The first one was that godless normative realism involves extravagant metaphysical claims which make it very implausible. Here I was surprised by the relevance of my recent work on God and abstract objects. Because Erik Wielenberg is a Platonist, he believes that moral values are abstract objects that have a kind of Platonic existence rather like mathematical objects like numbers and sets and so forth. He thinks that these abstract objects come to supervene or impinge upon physical states of affairs. So, for example, when two people love each other, the moral value (the abstract object) “goodness” comes to supervene upon that physical state of affairs. So my first objection to this view is that it is metaphysically extravagant in postulating this realm of causally effete, unconnected, abstract objects, whereas theism is more conservative because on theism God is a concrete object, not an abstract object. He is a person, and a person is not an abstract object. A person is an entity that is endowed with causal powers and therefore counts as a concrete object. So my first objection was that godless normative realism is more metaphysically extravagant than theism and therefore less plausible.

KEVIN HARRIS: Erik would have to back up in his work and his writing and defend Platonism first, wouldn't he?

DR. CRAIG: That’s what I thought. Yes. I said you have got to give us some argument for thinking that there is such a realm of causally unconnected abstract objects.

KEVIN HARRIS: Something is called Justice, and it is just hanging there. It is Platonic.

DR. CRAIG: It is hard to even understand the view. So that was my first objection. My second objection was that godless normative realism faces a number of formidable objections. Here I list three of what I call formidable objections. The first one is that its account of the supervenience of these abstract moral properties on physical situations is unintelligible. What I argued here is that Wielenberg believes that physical situations actually cause these moral properties to impinge upon physical objects. I said that is completely mysterious. His view is supposed to be consistent with scientific naturalism, and yet it ascribes to physical objects causal powers that are completely unknown to physics. So I characterized it tongue-in-cheek as a kind of voodoo metaphysics.

The second objection was that its account of objective moral duties is seriously flawed. Here I identify three problems with his account of moral duties. First, it doesn’t provide a basis for unconditional moral obligations. Remember on normative realism you just kind of weigh the outcome of your actions and you pick which action has the better value – that is the one you are obligated to do. But that is not an unconditional obligation to do that. That is an obligation that is conditional upon if you want to do what is the best thing. If you want to act morally, if you want to do the best thing, then that is what you ought to do. But that doesn’t give you an unconditional obligation to do that thing. By contrast, theism does. Any good robust moral theory needs to give you unconditional moral obligations and prohibitions.

The second objection I thought was very interesting, and that is that his account of duty precludes acts of supererogation.[1] There are certain acts that go beyond duty. They are over and above what duty requires. For example, to give up your life for the sake of some other person. That is a good act, but it is not your duty. You are not obligated to give your life for that other person. Such an altruistic act is above and beyond the call of duty, as they say. But on his view, you see, you are obligated to do whatever is the best thing. So you would be obligated to give up your life. It makes acts of supererogation impossible because you are obligated to do those things.

The third objection to his account of duty was that it precludes moral obligation by undermining the freedom of the will. He is a determinist. He thinks that mental states have no causal impact upon the physical brain states. Indeed, he doesn’t think that there really are mental states distinct from physical brain states. Everything that you decide to do is determined by your physical brain states, and those are determined by prior physical brain states so that everything is determined. But if there is no free will, moral obligation makes no sense whatsoever. How can you be morally obligated to do something that you are not able to do because you are determined? His commitment to what he calls the causal closure of the physical – that is to say that the physical brain states are causally closed to any influences outside the physical – I think completely undermines his view of free will and of moral obligation.

So the first objection was that the account of supervenience is unintelligible. The second one was that his account of objective moral duties is flawed in three ways. Then my third objection was that its account of moral knowledge makes moral knowledge impossible. Here I appeal to Alvin Plantinga’s evolutionary argument against naturalism. If our cognitive faculties are programmed by natural selection for survival rather than true beliefs then we can have no confidence that our beliefs are true including our moral beliefs. All we know is that our beliefs have survival value, but we can’t know those beliefs are true. So Plantinga’s argument, I think, undermines Wielenberg’s account of moral knowledge. We can’t really know the content of our moral duties or good and evil.

KEVIN HARRIS: Is that the first time that you have used that?

DR. CRAIG: Yes, it is! People have been asking for years: Why don’t you use Alvin Planting’s evolutionary argument against naturalism? It seemed to me that here was the perfect opportunity to do it because Wielenberg’s book, Robust Ethics, in which he lays out his view is divided into four sections. Section 1 is on the metaphysics of morals. This is his Platonism. But Section 4 is on moral epistemology or moral knowledge. He fairly invites this critique by Plantinga of his account of moral knowledge and how moral knowledge is even possible on this naturalistic view. So it was a great opportunity to use for the first time Alvin Plantinga’s evolutionary argument.

KEVIN HARRIS: How did he respond to these three things?

DR. CRAIG: Well, his responses to these objections were rather curious. They were by and large what I call “so is your old man” responses. That is to say, he didn’t really deny that his view has these problems. He just threw it back in my face and said, Theism has got the same problem so your view is no better than mine. So is your old man! That kind of thing. So, for example, remember I said his view is metaphysically extravagant because it has this realm of abstract objects that are causally unconnected with the realm of concrete objects.[2] And he said, But theism has this spiritual immaterial reality (God) which is different than physical reality. How can these be causally connected? How can the spiritual or the mental have any causal connection with the physical? That led to a discussion in the debate of the mind-body problem which then got pulled into the debate. Philosophy of mind. That just kind of shows how the debate expanded. I argued that although theism does face that challenge this is not as implausible and difficult as the connection between abstract and concrete objects because at least in the case of God or the soul and the physical these are both concrete entities endowed with causal powers and therefore could plausibly be causally connected.

KEVIN HARRIS: I am anxious to get to the point in the debate where the issue of the psychopath came up. What is the context there?

DR. CRAIG: Remember his original objection was that unbelievers have no moral obligations because they cannot recognize that these commands come from God and have authority. When I answered that using the example of the locked gate on the beach and the no trespassing sign, his response to this was psychopaths don’t have the ability to recognize moral authority and right and wrong and therefore they wouldn’t have any moral obligations. So the objection narrowed from unbelievers in general have no moral obligations on my view down to, These psychopaths, at least on your view, don't have any moral obligations because they can't recognize their moral duties. That was typical of Wielenberg in the debate. The goalposts kept moving. His objections kept morphing into something else as I answered them. In an academic debate that would be judged, such as you would do in college or high school, the debate judge would count that against the team that kept moving the goalposts because he would say you are shifting ground. You are no longer defending your position, you are shifting ground to a new position. You keep retreating. So in a formal debate that would lose points. That is what Wielenberg kept doing. He kept shifting from, say, believers in general now to psychopaths. My claim was that if psychopaths do have a sense of right and wrong and can recognize the difference then they will be held morally accountable just as they are in a court of law. This Cruz who killed those students in the Parkland school in Florida. If he is determined to recognize the difference between right and wrong then he will be found guilty. But if he is literally mentally ill and cannot recognize this then he will be found not guilty by reason of insanity like that fellow in the theater shooting in Denver who was judged to be mentally incompetent and therefore isn't guilty by reason of insanity. So I just see this as no objection of a serious sort to divine command ethics. I thought this was not a very plausible objection.

KEVIN HARRIS: Is there a difference between being morally obligated and morally culpable? If you don't have moral obligations then you are not morally culpable.

DR. CRAIG: I think that is a very good point that occurred to me as I contemplated how to respond to the objection. I could well imagine a theist saying that God has issued these moral commands to everybody in general and therefore everyone is under the obligation to obey the command. But when some people don’t obey it, like mentally insane people, they are not morally culpable for living up to their obligation. They are obligated, as you said, but they are not culpable. One could think of an analogy in the law. Isn’t everybody under the obligation, say, to obey the speed limit or to have a gun permit or something like that?[3] But if the mentally deranged person does it, it is not as though he has no obligation to do those things. He is still under the law. He is a citizen of the state. So he is under those laws, too. But he is found not culpable when he carries a gun without a permit or drives over the speed limit because he is mentally incompetent. So I think you could be onto something there. This is an area that I think I would like to explore with those who specialize more in ethics. Couldn’t there be a kind of obligation that arises in virtue of divine law but then certain lawbreakers, which the psychopath is, isn’t culpable for his law-breaking in the way that a normal person would be?

KEVIN HARRIS: Keep us informed and updated on whether this will become a book because to be able to pore over the pages of this debate – a deep debate – I think would be helpful.

DR. CRAIG: I think you are absolutely right. The book will repay study and will include responses to the book by two philosophers that Wielenberg will pick and two philosophers that I will pick. I am going to pick my colleague J. P. Moreland and David Baggett for my two respondents. So it should be a good discussion.

KEVIN HARRIS: That should be good.[4]