The God Particle

July 09, 2012 Time: 00:23:45

Summary

Dr. Craig discussed this amazing discovery and analyzes Michio Kaku's commentary. Does this discovery somehow disprove God?

Transcript The God Particle

Kevin Harris: Welcome to Reasonable Faith. I'm Kevin Harris. The minute the news broke that the “God particle” had been discovered I got on Skype with Dr. Craig from his office, and we discussed it. Let's go right to that conversation.

Well, Dr. Craig, this has been called the Holy Grail of physics and, you know, you can't go anywhere without running into this news story on this, what has been called the God particle. Now, we'll get into why it's called that in just a moment, but what do you think about this discovery, and is it in fact the Holy Grail of physics?

Dr. Craig: Well, it's one of those wonderful instances in science where a prediction made purely on the basis of theoretical physics receives an empirical confirmation, and that is always very exciting when that happens. It shows that the language of nature is the language of mathematics – that the world is endowed with this orderly rational structure so that theoretical scientists making predictions can actually tell us about the universe, and lo' and behold the experimentalists go out and find out that it is actually just as the theory predicted. And that's what happened in the case of this particle, which is part of the standard model of subatomic particle physics.

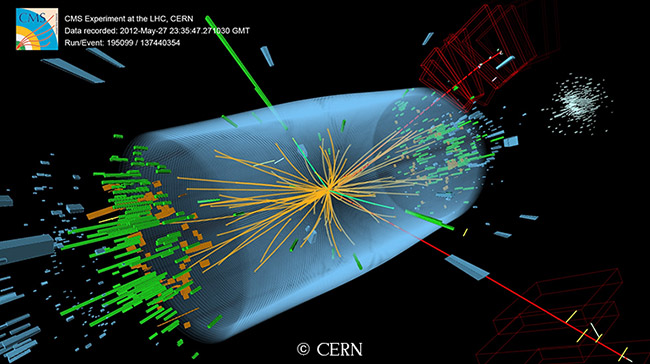

Kevin Harris: We've been keeping up with this huge atom-smasher in Europe for quite some time, the CERN. This has been called the most powerful machine on earth – just miles long. And this has been necessary to slam these particles together to discover this?

Dr. Craig: Yes, that's right. In the standard model of particle physics there are various subatomic particles that are postulated to exist, things like quarks and electrons and photons and neutrinos and so forth. And the last of the particles that is part of the standard model to be empirically confirmed is this Higgs boson which is named after Peter Higgs, the physicist who predicted it's existence back in 1964. The difficulty with detecting the Higgs boson is this particle is a very massive particle, and therefore requires enormous energies in order to create in these colliders. It also decays almost immediately so that before the residue gets to the detectors, it's gone. And so as a result it has taken an enormous amount of time, money, and effort in order to finally confirm the existence of this final particle in the menagerie of particles that make up the standard model in particle physics.

Kevin Harris: So, Bill, why is this called the God particle? Certainly the press has picked up on that.

Dr. Craig: That name comes from Leon Lederman who in 1993 wrote a book called The God Particle. And I think that this has been unfortunately very misleading to many laypeople. The particle isn't mean to supplant God or to substitute for God. The reason Lederman called it the God particle is for two reasons. First of all, this particle underlies every physical object that exists. It is what gives every physical particle and every physical object the mass that it possesses. So it's like God in the sense that it underlies the physical existence of every object in the universe. In Christian theology God similarly conserves the universe in being.

Secondly, like God the particle has been very difficult to detect. It's not detectable by the five senses; it has been exasperatingly, frustratingly difficult to find. And that also speaks to us, I think, of the hiddenness of God. In discussions on the problem of evil, for example, it is very often a matter of discussion why God seems so hidden, why he seems so absent in times of suffering. We would expect, perhaps, his existence to be more manifest, for him to make himself clear to us, and yet he doesn't.

And so I really like this nickname “the God particle” because it highlights two very important features, theologically, of God. Namely, God's underlying the existence of the entire universe; he conserves it in being, he didn't simply bring it into being initially, but he sustains it in being.[1] And without his upholding power the universe would be annihilated in an instant. And then secondly, it also informs us that even though God's existence may be hidden, that is no evidence that he doesn't exist. The Higgs boson has been there all this time even though we haven't been able to detect it. And so this is a wonderful illustration that the absence of evidence isn't evidence of absence. God is a reality that objectively exists, even if sometimes he's frustratingly hidden.

Kevin Harris: I want to go to this clip from CNN from Michio Kaku, Bill, which I think sums up some of why it's called the God particle:

Michio Kaku: Now the God particle – we physicists wince when we hear those words – but there's some truth to that. The Bible says that God said “let there be light” and there was the universe. Physicists say there was a Big Bang, an explosion, 13.7 billion years ago; but what was the match? What was the fuse, what was the spark that lit the Big Bang? Where did the bang come from in the Big Bang theory? We're clueless, we didn't know. And that's where the Higgs comes in.

Kevin Harris: What are some of the points that you garner from this clip?

Dr. Craig: Well, first it's interesting that he says – very rapidly, but he says – physicists wince at this nickname the God particle. Now, why is that? Why would physicist wince or be uncomfortable with the name the God particle? Well I think the reason is because the Higgs boson and the standard model of particle physics is not the ultimate answer with respect to the origin of the universe. It's a theory that only applies to the universe at relativity low temperatures. But as you go back in time the universe becomes increasingly dense and increasingly hot. And as these temperature becomes incomprehensibly high the standard model of particle physics no longer applies. The standard model is an attempt to explain the dynamics of the particles governed by the subatomic strong force, the subatomic weak force, and the electromagnetic force; gravity is just left out of the standard model. But when the universe is very dense and very hot, as you get back near the beginning, the standard model doesn't apply because it's too hot, too dense, for all of these forces to exist separately, and they become unified into a single force for which we do not yet have a theory. This is the so-called “grand unified theory” that physicists are seeking, or a GUT. And the GUT era would precede chronologically the era in which the standard model of particle physics describes or applies. And so the standard model isn't the ultimate answer. It's not like God; it's not the final answer to why things exist. You need to go back earlier than that to the GUT era to have a grand unified theory in which the strong, weak, and electromagnetic force will be unified or symmetrical.

That, however, still isn't the final answer, Kevin, because as you go back even closer to the beginning of the universe the temperatures continue to increase, the density increases, and now you have to incorporate gravity into your physical description. And when you get prior to the so-called Planck time – ten to the negative forty-three seconds after the beginning of the universe – then you have the theory of quantum gravity in which gravity is united with these other forces of nature and you have a single force, a single particle which describes the universe at this very early era. And we don't have any theory yet to describe this quantum era, this period of quantum gravity.

So to reverse the backward extrapolation and go forward again in time, what you have first is this Planck era during which you have a quantum gravity theory. Then that symmetry is broken and gravity separates out from the other forces, and that is your GUT era, or the grand unified theory. Then as the temperature goes down the symmetry is broken again and the three forces of the weak force, strong force, and electromagnetic force separate out, and then you get the standard model era in which we presently live.[2]

So I think you can see that this is just one step on the way toward understanding the physics of the early universe. And therefore I'm mystified when Kaku says that the Higgs particle is the match or the fuse that lit the Big Bang. That's just simply inaccurate. The standard model of particle physics doesn't apply during the GUT era and certainly not during the Planck era when you have a quantum theory of gravity. So we're talking about a physics that is much later, relativity speaking, than the earliest part of the universe. The universe was already expanding, already cooling, by the time you get to standard particle physics. This is by no means the match or the fuse that lit the Big Bang. It's just bewildering that he would say such a thing.

Kevin Harris: Let's go to a second clip from him from CNN.

Interviewer: This isn't just science; this is how science may actually disprove religion? Because you said you cringe when you hear “God particle.” Is that where we may be headed with this?

Michio Kaku: Even more than that. Realize that the Higgs boson takes us to the instant of creation itself. And we can run the video tape before the Big Bang. We can talk about the universe before the creation of the universe itself. If our universe is a soap bubble of some sort and it's expanding there could be other soap bubbles out there, other universes. And so this is where the next step beyond the Large Hadron Collider comes in. We're going to look for evidences of a pre-Big Bang universe, perhaps the existence of other universes, and then of course we have the question that everyone asks me: is Elvis Presley still alive in another parallel universe?

Kevin Harris: And his answer to that, by the way, is, well, possibly because of the multiverse and the possibilities opened up by that.

Dr. Craig: What he starts off with, Kevin, is by saying that this disproves religion; and he says, “more than that.” Now here, honestly, I don't know what in the world Kaku is thinking about. How in the world does the standard model disprove religion? As I say the standard model doesn’t even kick in until the expansion is well under way and the temperatures have cooled sufficiently, and this does in no way supplant the role of God in the universe.

The Higgs boson and the field, the Higgs field that give mass to the particles that are moving through the field, are contingent realities. These are part of the physical universe that didn't even exist until the universe had sufficiently cooled and expanded. They're not necessary. They're not eternal in their existence. So it's just silly, frankly, to say that this somehow disproves religion or worse.

And when he says that the Higgs boson takes us back to the instant of creation, that's simply scientifically inaccurate. It does not. To do that you need a quantum theory of gravity, and the standard model doesn't incorporate gravity at all.

Now when he then goes on to talk about going back before the Big Bang, here he is talking about speculations and models that have nothing to do with the current discovery that we're celebrating at CERN. He has changed the subject now, and, in speaking of our universe as being a bubble in a much wider universe and so forth, he is talking about eternal inflationary models of the universe in which there is this sort of mother universe which is expanding, and within the womb of this mother universe there are forming these little bubbles which are then expanding themselves, and we are one of these bubbles. Our universe is a tiny bubble within this larger expanding universe. And as Kaku, as a professional physicist, must know, the Borde-Guth-Vilenkin theorem applies to this wider mother universe and shows that it cannot be past eternal; it had to have a beginning. So you haven't avoided the absolute beginning of the universe that was postulated by the standard model in Big Bang cosmology at all. Vilenkin in his most recent paper published in April of this year showed that eternal inflationary models as well as cyclic models and other static models cannot be eternal in the past.[3] Vilenkin concludes with the remarkable statement,[4] and I'm quoting from him here: “For all we know there are no models at this time that provide a satisfactory model for a universe without a beginning.”[5] So I think Kaku is simply misleading here when he gives the impression that we're somehow on the verge of restoring an eternally existent universe.

Kevin Harris: It eludes me as well, Bill, why speculation and discoveries on how the universe works somehow disproves God.

Dr. Craig: Yes, it's bizarre, Kevin. I think what our listeners need to understand is that the role of this particle that has now been confirmed to exist is to set up a field, a Higgs field, that permeates all of space. And as the other particles postulated by the standard model move through this field they acquire their various masses. So, for example, a photon has zero mass but an electron has a very tiny mass, and that's all that this amounts to. It just explains why particles moving through the field acquire the values they do of their various masses. But this has, so far as I can see, no theological implications at all.

I've said, Kevin, that as a result of my experience with people like Lawrence Krauss, Stephen Hawking, and certain others, we can no longer trust these men to tell us about the implications of modern scientific theories, and especially about their philosophical and theological ramifications. And I think we have to add now Michio Kaku to that list. There is an agenda, perhaps a naturalistic or anti-religious agenda, that drives these statements suggesting that somehow the discovery of the final particle in the standard model – that everyone has always assumed to be true – somehow disproves religion, or worse.

Kevin Harris: And that is the impression that the press sometimes gives when you read these headlines. “Oh, the particle has been discovered, therefore God does not exist.” I think there are two reactions, Bill, from people of faith or from Christians, and that is: one is just: “Ah, ignore the whole thing,” and the other is, “Well, does this actually cast doubt? Are they saying what I think they're saying here?” When this trickles down to the layperson and to the people at large the headlines, without even reading the articles, can say volumes and make theological ramifications.

Dr. Craig: Yes, that's right. And then when you get deliberate explicit statements like those by Michio Kaku that just confirms those impressions in the mind of laypeople. I think it's important to keep in mind, Kevin, about this discovery that it's not as though something new has been discovered. Rather the standard model of particle physics has been assumed, it's part of the standard physics for the universe. It's just that this is the last particle in the standard model to be empirically detected – that's all. So nothing has changed. Everyone has assumed that the theory is correct. We just now have confirmation that it's correct, and so one can proceed as usual with the work. Nothing has really changed.

Kevin Harris: Let's play one more clip from Kaku. He says some interesting things in this clip from CNN:

Michio Kaku: We think that originally the universe was a gas of particles with no mass at all. Think of a crystal; beautiful crystal, totally symmetrical, but useless. It exploded, and the shattering of this crystal gave us all the masses of the particles today – the electron, the proton, the neutron, the atom – why do we have a nucleus, why do we have a proton? Because they have masses. So the explosion of the particle broke the original perfect symmetry of this crystal, giving us the broken world we see today of planets, stars, galaxies, you, me, even love.

Kevin Harris: Now he confirmed a lot of what you say there, Bill, as far as how this all works.

Dr. Craig: Exactly. What he's talking there is about the various phase transitions that the early universe goes through as it cools and expands that breaks these symmetries. So initially you have a completely symmetrical state in which these four forces of nature – gravity, the strong force, the weak force, and electromagnetism – are not distinct forces, they're all unified in this single force during the Planck era. That needs a quantum theory of gravity to describe, which we don't have. Then as the universe continues to expand and continues to cool, gravity breaks out, the symmetry is broken, as he says, and you now have a distinct gravitational force.[6] This is the era described by the grand unified theory of physics, the GUT era, and again, unfortunately, we don't have a physics of that era. Then after the GUT era the universe continues to expand and cool, the symmetries are broken, again the universe goes through another phase transition, and the other three forces emerge as distinct forces – strong, weak, and electromagnetic – and that then gives us the standard model of particle physics that we know and love today, which includes the Higgs boson and the field for which it's responsible that gives the mass to the other particles that are moving through this field. So he has correctly characterized for us there the symmetry breaking that goes on in the early universe, but in connection with his other statements it might give the impression that it was the Higgs boson that was somehow there at the beginning, at the instant of creation, as he says, or even before the Big Bang, that somehow explains how all of this happened. And that would be a gross misunderstanding.

Kevin Harris: It's interesting that he even mentioned that love is a result of this [laughter]. I mean, that's kind of a philosophical speculation as to the nature of love.

Dr. Craig: Right, yes, that's a good point, Kevin. I hadn't thought of that. I took this to be just a rhetorical dash that often scientists who are speaking to the popular media might make, that the physics explains everything. But if you take that seriously that would suggest that love is nothing more than a sort of electro-chemical reaction in the brain, and has no more significance than that. And that would be to endorse materialism, physicalism, determinism, and so forth, which are philosophical positions, again, that go quite beyond what the science tell us.

Kevin Harris: Let's wrap this up in a bow, Bill. It's an exciting discovery, it has shown the usefulness of making predictions and then discovering that in fact what was predicted scientifically can be discovered.

Dr. Craig: It certainly does show us the rational mathematical structure of the universe in which we live, which I think bespeaks the rational structure that God has infused into creation so that theoretical physics using mathematics can explore nature, make predictions which the experimentalists can then go out and confirm.Moreover I think that the so-called God particle does teach us those two lessons that I mentioned earlier. First of all that God is the ground of existence of everything that exists, not only you and me and the things that we see around us, but even the Higgs boson, the Higgs field, and these other subatomic particles themselves are all contingent realities that are sustained in existence by God. And secondly, even though God may often seem hidden and we cannot detect his hand or presence in our lives, that doesn't mean that God isn't there providentially directing the course of world history toward his previsioned ends.[7]